Fresh Flour Power

01

The Seven-Year Itch

Blair Marvin and Andrew Heyn bought Elmore Mountain Bread, a bakery that sits on a wooded mountainside in the middle of Vermont ski country, in 2002. They successfully sold hearth-baked sourdough breads to customers at farmers’ markets, supermarkets, and nearby restaurants until 2011, when both members of the married couple began to feel restless—a “seven-year itch,” they said. They thought about selling the business and setting out in search of something different to do with their lives.

But then a package arrived. Their friend Dave Bauer, owner of Farm and Sparrow bakery in Asheville, NC, shipped Marvin and Heyn a box filled with flours he had milled himself, on his Austrian stone mill, for them to test in their breads. Even before they baked with the new flour, they could tell it was something special. “We were so used to working with flour that was dry, dusty, and had no aroma,” Heyn said. “[Bauer’s] flour looked creamy, felt fatty from the germ oil, and had an aroma we had never smelled before.” The baguettes and country French loaves they made using the flours were not just good, they were revelatory.

Until then, the breads at Elmore Mountain were made with commercially milled white flour, supplemented with a small amount of commercial whole-wheat flour. They wanted to use more whole-wheat flour, both for flavor and added nutrition, but it adversely affected the texture of their breads. Bauer’s flours, however, were milled and sifted in such a way that they behaved and tasted somewhere in the delicious middle ground between white and wheat flour. The ethereal loaves made with these fresh flours hinted that it was possible to bake breads with less-refined flours that had great texture, phenomenal wheat flavor, and most of the nutritional benefits of breads made with straight whole grains.

They were not alone in this realization. There is a strong but quiet revolution currently under way in the world of American bread making: milling wheat and other grains into flour in-house. San Francisco’s Chad Robertson, who rose to fame with his bakery Tartine, is installing a mill at his new location, the Manufactory, to grind flour for his famous breads daily. Just across town, at (the aptly named) The Mill bakery, Josey Baker (also aptly named) does the same. Chefs like Philadelphia’s Marc Vetri, Dan Barber of Blue Hill at Stone Barns, and Chris Bianco of Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix are milling fresh flour for use in pasta, pizza, and breads. All of the Eataly bakeries are using flour milled daily at Wild Hive Farm in upstate New York.

“Why go to the extra trouble of milling flour yourself? The short answer: more delicious bread that’s better for you,” wrote Baker in an email.

And this isn’t a revolution confined to professional bakeries. Whether through innovative home-milling technology (think: KitchenAid mixer attachment) or simply buying fresh-ground flour from a local bakery or online, home cooks can make bread—or waffles, or pasta—with great texture and intense wheat flavor with relative ease.

02

Why is Fresh-Ground Flour Better?

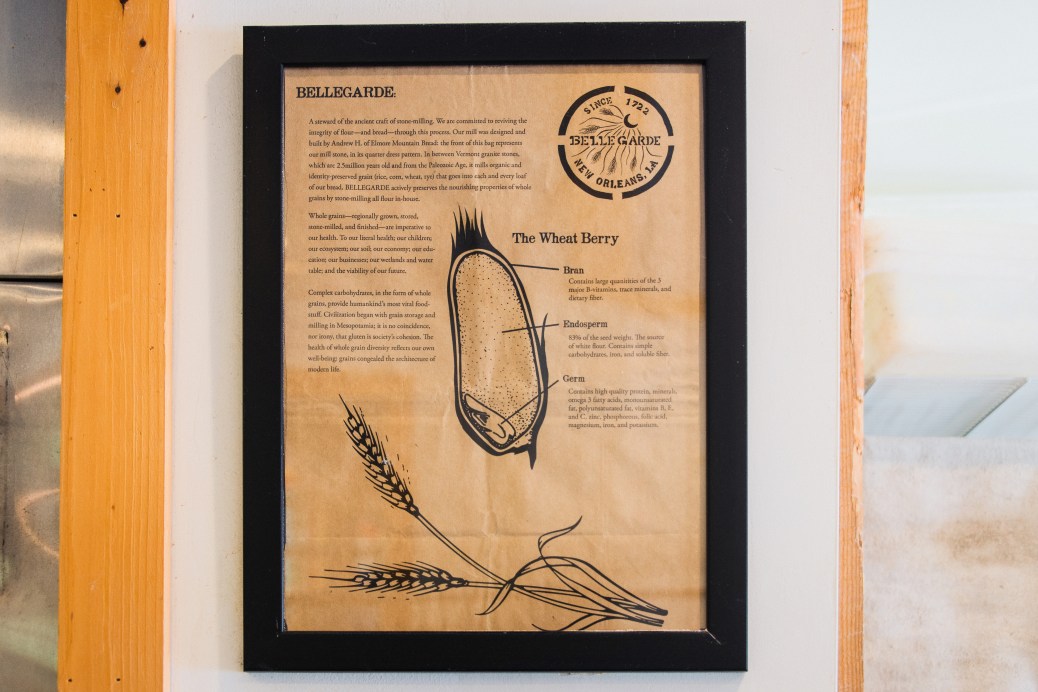

A grain of wheat is made up of four parts. The bran, or seed coat, is a dark-colored fibrous shell that surrounds the kernel completely, protecting it from the elements or attack by pests. Just beneath the bran sits the aleurone layer, chock-full of oil, minerals, vitamins, enzymes, and proteins. This is where most of the nutrition and flavor in wheat are found. The aleurone layer is the outermost part of the endosperm, the starch- and protein-rich energetic core of the grain, comprising most of the grain’s weight and volume. Finally, at one end of the seed sits the embryo, or germ, the dormant wheat plant waiting for its day in the sun. It, too, is rich in oils and flavor.

When wheat berries are ground into flour in factory mills, they are immediately separated into their component parts. White all-purpose and bread flours contain practically no bran or germ; they are made almost entirely of ground endosperm. Most so-called whole-wheat flour made commercially is actually reconstituted after the fact to achieve the ratio of components found in the whole grain.

The structure and chew of bread is created, for the most part, when two proteins present in wheat flour are hydrated and come together to form a network of gluten. But bran is tough and sharp, and unlike the rest of the grain, it doesn’t soften when hydrated. This means that bran’s sharp edges slice apart gluten strands like microscopic razors, which is why things like crackly-crisp baguettes and ethereal croissants—not to mention plush abominations such as Wonder Bread—could not exist until we found a way to easily and economically remove bran from flour.

Because of how closely the bran mingles with the aleurone layer and the germ, it’s also where much of the flavor and nutrition resides; generally speaking, the more bran you remove, the less complex the flavor of the bread. This is why whole-wheat flour has the potential to be the most flavorful (and healthful) flour available. But if you are like most home cooks in America, one package of whole-wheat flour can sit on your shelf for a very long time. And it’s this storage time that can sap your flour of its flavor—and its nutrition.

There is a lack of double-blind studies proving conclusively that the flavor and nutritional benefits of fresh-milled flour are greater than those of flours stored for extended periods of time before use. But as Dr. Steven Jones, director of the Bread Lab at Washington State University, told me, it’s only because funding for doing definitive studies has been slow to materialize. “The short answer is, it is not a marketing ploy. There are real flavors that are lost within a short time [in commercial flours]. We’ve done informal blind tastings, and the difference between flour that was freshly milled and flour that had been stored for a while was clear to everyone.” We’ve done similar tastings in the test kitchen at America’s Test Kitchen, with very similar results. Breads made using commercial whole-wheat flours all had a bitter undertone that was absent in those made with fresh-milled flours.

When it comes to nutrition, while “minerals and many macronutrients tend to be stable over time, the micronutrients vitamin A, vitamin E, some B vitamins, and unsaturated lipids in fresh flour are all highly susceptible to oxidation from air or degradation through exposure to light,” said David Killilea, a biochemist at Children’s Hospital in Oakland, who is collaborating with Jones. What does that mean? With oxygen, with light, and with time, flour loses many of its important micronutrients.

“With commercial flours, it may be difficult to determine how long ago they were milled and how the product was handled,” he added. “Under good conditions, commercial flours could still have all the inherent nutrients available. But with freshly milled flour, you know that you’re getting all of the micronutrients in their full amount and natural form.”

Here’s where milling in-house or at home proves beneficial:

1: Fresh-ground flour tastes better than commercially ground flour. Because fresh flour can and should be used immediately, there isn’t time for the flour to become oxidized and rancid, or to lose its flavor or nutrients. Because after grinding flour in-house or at home, you must sift it, you can sift it in a way that retains much of the flavorful elements of the flour.

2: Fresh-ground flour can bake loaves that have more of the characteristics we love in bread than loaves made with commercial whole-grain flour. How? Because when fresh-milled flour is sifted, enough of the sharp-edged bran is removed to allow the flour to create a solid gluten network while still retaining most of the flavorful elements. (You can sift commercial whole-wheat flour to similarly help with structure in your baked goods, but due to the time since milling, this flour is likely to be less flavorful.)

03

Stone Mill Engineering

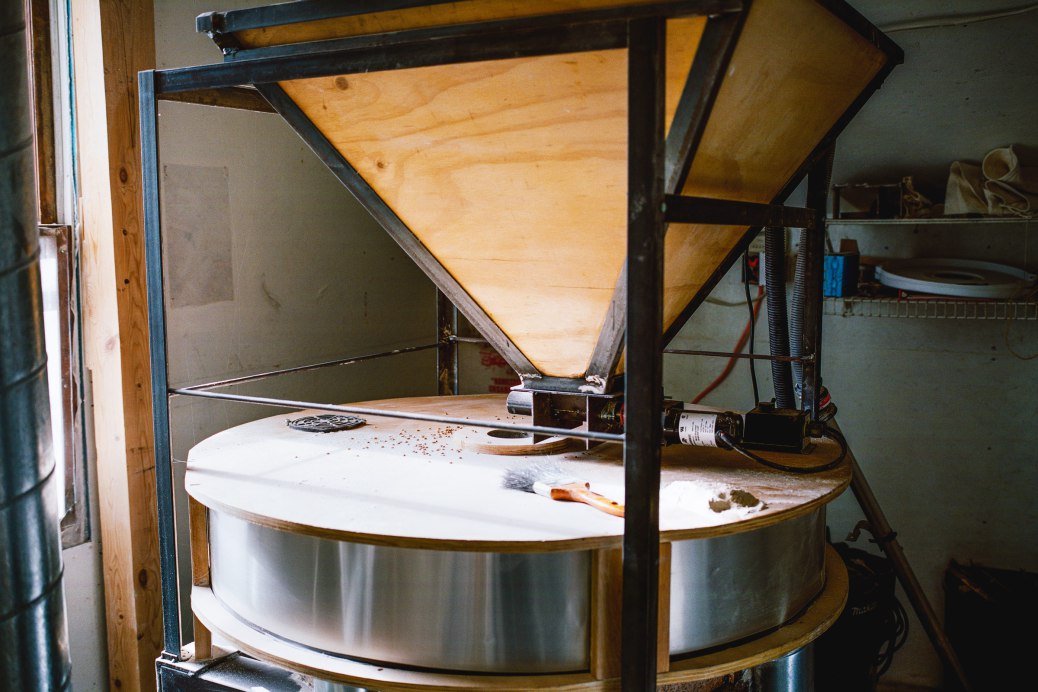

For Marvin and Heyn at Elmore Mountain Bread, getting to a place where they could regularly produce bread made with fresh-ground wheat flours required that they obtain a mill. They had a few options: They could buy and transport a mill from Europe, where many bakery-scale mills are made. They could acquire an off-the-shelf American mill, though the only ones available were on the small side. Or they could design and build their own. Building their own mill would be a less expensive option and would allow them greater control over the quality of the flour they could produce. Besides, Heyn was the son of an engineer and a natural-born tinkerer himself, so the idea of designing a mill from scratch was appealing. He got to work.

The pair of pink granite stones at the core of Elmore Mountain’s mill are 3 feet across and weigh 700 pounds each. Most stone gristmills consist of two disc-shaped stones stacked upon one another. The lower one is fixed in place, and the upper one rotates. Grains are fed into the mill through a hole in the center of the upper stone and are propelled outward by centrifugal force between the stones, to emerge as flour at the outer edges.

Simple millstones have flat, coarsely textured faces that crush the grain into relatively uniform particles. Flour made in this sort of mill can be sifted to remove the largest, most resilient bran particles, but smooth stones do not discriminate effectively between flour components and tend to produce darker flours with a large amount of fine bran present.

Elmore Mountain’s stones instead are “dressed” with channels and grooves designed to help separate the bran from the remaining kernel to produce a flour that is more amenable to sifting. Once milled, the flour at Elmore Mountain Bread is then piped, via a fan, into the sifter nearby. Once there, the flour first passes through a 60-mesh screen (meaning 60 wires per inch in both directions) to remove the coarse bran. A second set of 80-mesh sifters pulls off the middlings, or the fine bran with a small amount of coarse endosperm semolina mixed in. What makes it through both sets of screens is their base flour—a silky, rose-hued product.

04

Sorting Out The Bread

Initially, Marvin and Heyn blended the fresh-milled flour with commercial white flour, thinking they would only gradually increase the amount of the fresh stuff until it was the only flour in use. But one day Heyn made their country French dough using 100 percent of their own fresh-milled flour. And while it would take time before they sorted out the mechanics of how best to work with these flours exclusively, for them, there was no turning back.

“The first thing I noticed was the aesthetic,” says Marvin. “The color and texture of the crust was so rich and vibrant. Same thing for the crumb. And the change of the flavor was nothing short of amazing. The complexity of flavor and the way it lingered was something very new to me.”

Beyond the baguette and the country French loaf, Elmore Mountain makes more than a dozen different breads on a rotating basis, all of which use fresh-milled wheat flour as the base. There’s an airy ciabatta that adds in some house-milled spelt. The anadama bread uses fresh-milled cornmeal and Vermont maple syrup. A brewer’s bread uses malted barley and beer from a local brewery. And there are a variety of focaccias, topped with things like caramelized onions or Vermont cheddar.

Elmore Mountain’s customers soon came along for the ride. Interestingly, it wasn’t just the improvement in flavor or the promise of greater nutrition that convinced many of them to stick with Elmore Mountain Bread, but the fact that the flour—and the grains it was milled from—was local.

“I made it my mission to explain to anyone who would listen,” Marvin said, “that [milling in-house] let us buy more wheat and specialty grains directly from our local farmers, essentially passing the profit on to them and allowing them to expand their growing capabilities . . . laying the building blocks for reviving our local grain economy.”

05

Back to the Test Kitchen

After spending time at Elmore Mountain Bread, I was excited to mill flour to bake with back home in Boston. I am an enthusiastic baker—and a senior editor at Cook’s Illustrated by day, where I have developed more than a dozen bread recipes for the magazine. I’d milled flour here and there, but now I really got it and was jazzed to see how using fresh-milled flour would transform my own baking.

I decided to develop four recipes, with different degrees of difficulty, from an easy Buttermilk Waffle to a more rustic Country Loaf (with fresh pasta and focaccia in between). To make these recipes, I knew I wanted to offer differing levels of flour difficulty as well. For the noncommittal bakers, all of these recipes can be made with commercial whole-wheat flour. All you need to do is sift it (except for the waffles; those are good as is). The somewhat more committed bakers can buy fresh-ground flour from a local bakery, if you’re into that kind of thing, a local market, or in one of many places online. You will need to sift this flour as well. For the fully committed: You’ll need to get a mill. Luckily, there are many options for the home baker.

I started my testing with mills. Long ago, I’d tried using a hand-cranked mill (the sort that clamps to the end of a counter and looks a lot like a meat grinder), but it left me with flour that was too coarse for nice bread (and sore arms).

I’d also used powerful blenders with sharp blades—such as a Vitamix—to grind grains into flour before. (The Vitamix sometimes comes with a dedicated blender bowl that’s specially designed to process dry ingredients.) But blenders can only process a few cups of grain at a time without overheating the flour, so they aren’t ideal if you want to mill flour regularly.

The most economical option for home milling is an attachment for a stand mixer (provided you already have a stand mixer, of course). A few mixer manufacturers sell attachments for milling, but the only one that uses actual stones to grind flour is the Mockmill, a third-party attachment for KitchenAid and Kenmore stand mixers that costs around $200. I tested one myself and found it to do a good job of milling wheat, despite having stones only a few inches in diameter. It processes about 60 grams of wheat per minute and doesn’t heat up the flour much, as long you don’t grind more than a kilogram or two of wheat at a time. This is my recommendation for an entry-level stone mill for someone who wants to jump into the world of fresh-milled flour.

But given my newfound passion for fresh-milled flour, I knew there was only one real option for my own baking: a dedicated tabletop mill. There is a panoply of styles using different means to grind the flour, from metal plates (burr mills) or concentric rings of sharp metal teeth (impact mills). But the Cadillac of tabletop flour milling is the stone burr mill, like the KoMo mill I bought for $500. These are essentially scaled-down versions of professional stone mills. Stone mills are the slowest to heat up and can be run for relatively long durations without degrading the flour. And the grind size on most stone mills is easily adjusted, allowing them to be used to produce everything from coarsely cracked grains to fine flour. My KoMo mill is also a thing of beauty, with a polished beechwood housing designed to mimic bakery-scale European mills.

Next up? I’d need a way to sift the flour I milled. I tried using a standard fine-mesh kitchen strainer (which is usually 30 wires per inch in both directions), but that only removed the largest bran flakes (about 5 percent of the total flour weight), and the flour it left me was far too coarse to produce a light, airy loaf. To get something closer in texture to Elmore Mountain’s standard flour, I used 50-mesh drum sifter (available here and here), which removed a lot more of the bran and coarse middlings, leaving me with a fine, evenly textured flour that represented 85 percent of the total weight of the grain.

And so onto the recipes. The waffles are an easy entry point into working with fresh-milled flour, since they can be made without a mill at all, using wheat berries and a high-powered blender. The remaining recipes all use milled flour and a 50-mesh drum sifter to achieve the right texture. The pasta has a delicate texture with just a hint of bite as well as a nutty flavor. I made two focaccias, one with rosemary, fennel seed, and sea salt, and another with cherry tomatoes and pecorino. (The focaccia dough uses a bit of high-protein all-purpose flour to keep its texture open and crisp.) Finally, I created a long-fermented country boule loaf as a tribute to Elmore Mountain’s breads, with a little twist of my own. (All four of these recipes can be made using store-bought whole-wheat flour if you don’t have access to a mill. Just try to use a freshly opened bag for the best possible flavor.)

06

Recipes

07

Tips on Buying and Using Whole Grains

Here are some really useful tips that writer and baker Andrew Janjigian has picked up on his fresh-milled flour journey. But you don’t have to stop here. Talk to us in the comments and let us know about your questions, experiments, recipes, and more.

BUYING GRAINS

Nowadays, many supermarkets carry whole grains in 1-pound bags, though selection may be somewhat limited. Food co-op bulk bins are a good place to find whole grains in larger quantities, and the store will likely be glad to order 25- or 50-pound bags for you. (Since they can usually just add it to their regular deliveries, this is an excellent way to avoid the shipping costs associated with ordering heavy items online.) And just about any grain you might want can be ordered online in quantities small and large.

If you live in parts of the country that grow grains, you can even ask a local farmer if he will sell you grain directly. It used to be the case that most wheat was grown in the wheat belt running north to south from Alberta, Canada, to central Texas, but nowadays grain is grown from as far west as California and Washington state and as far north and east as Maine. Where I live (in Massachusetts), we even have a grain CSA that lets you buy a share of a local grain harvest each year.

TYPES OF GRAINS TO MILL

WHEAT

If you are milling wheat for bread baking, you’ll want to focus on hard red wheats, which contain substantial amounts of gluten-forming proteins. (Hard wheat grains are hard because of the high amount of protein they contain.) Winter wheat is planted in the fall, when it sprouts and then goes dormant during the winter months before growing again in the spring. Spring wheat is planted in the spring after last frost, usually in northern areas where winter temperatures are too harsh for overwintering wheat. (Both winter and spring wheats are harvested in the fall.) Hard winter wheat contains anywhere from 9 to 14.5 percent protein, and hard red spring wheat ranges from 11.5 to 18 percent protein.

Soft wheats (red and white) make flours destined for pastries, crackers, and snack foods. They contain 8 to 11 percent protein. You can use flour milled from soft wheat to make bread, but it would likely need to be combined with bread flour for adequate structure.

RYE

Rye is a distant relative of wheat and does not contain gluten-forming proteins, so it cannot be used by itself to produce airy, lightly textured breads. But it does contain sticky polysaccharides known as arabinoxylans that act somewhat like gluten to give rye breads structure and allow them to be leavened by yeast or sourdough cultures. It is arabinoxylans’ ability to bind up to four times as much water as wheat flour that give German and Scandinavian 100 percent rye flour breads their unique consistency and ultralong shelf life. (Elmore Mountain, like many other bakeries, likes to add a small amount of fresh-milled rye flour to its breads for another layer of flavor and to moisten the crumb. My country loaf recipe contains 5 percent rye for the same reason.)

ANCIENT GRAINS

So-called ancient grains such as emmer, einkorn, Khorasan, and spelt are all close relatives of wheat. (The Italian grain farro is typically synonymous with emmer and can be found in many supermarkets.) They all contain gluten to varying degrees and can be used on their own to make breads with relatively open structure.

OTHER GRAINS

Barley and oats are distant relatives of wheat that are often milled and used in breads. Barley is more closely related to wheat, but none of these grains contains gluten and must be combined with wheat flour to make a decent loaf.

Corn is another grain that can be milled at home. Most mills recommend against milling popcorn because it is too hard, so to make cornmeal or corn flour, you need to start with softer-kerneled flint or dent corn (which you will probably need to special order). Elmore Mountain makes a delicious corn focaccia with 15 percent corn grits mixed into the dough.

You can even grind rice or beans into flour using a mill. In fact, the only dried foods you cannot grind using a mill are highly oily things like coffee beans, nuts, and seeds.

STORING GRAINS

Storing whole grains is as simple as keeping them cool, dry, and away from pests. Small quantities are best stored in jars or snap-top containers; I like to keep larger amounts in clean, sealed 5-gallon plastic pails from the hardware store. Protected from heat, moisture, and pests, whole grains will keep well for a year or more.

Field Photography by Andrew Janjigian.

Test Kitchen Photography by Daniel van Ackere.

Food Styling by Lindsey Chandler and Kendra McKnight.