In the Weeds

01

Moss Landing, California

Mike Graham has seven kids and ten tanks of dulse.

His teenage son picks the surplus seaweed from the tanks and packs it in seawater. His wife packs the seaweed (and the baby) in the car and drives it to restaurants in Monterey and Pacific Grove. Other bags of seaweed are sent north to San Francisco and Oakland. A few ice-packed boxes are shipped to New York.

It’s a small operation, but it’s currently the only one in California farming seaweed for human food. That could soon change.

Seaweed consumption in the United States is booming as more chefs and consumers become interested in its nutritional and sustainable aspects and as farming innovations are spurred by researchers like Graham, owner of Monterey Bay Seaweeds and a professor of ecology at the Cal State University campus at Moss Landing, where his tanks of seaweed are located.

The plants grow exceptionally fast (a pound can turn into two pounds in a week), with no inputs other than seawater and light. And they have high proportions of protein, the ability to grow large yields in small spaces, and the potential to play a major role in helping meet the nutrition needs of a booming human population.

Today, seaweed farming is taking place both in experimental onshore farms and in the ocean. Both are on the brink of being able to create new seaweed varieties, with new farming methods, for new culinary uses, resulting in a new food source that, in some cases, can even improve the environment as it grows. Seaweed is currently a $5 billion industry and is projected to hit $20 billion in the next five years. Graham expects his production to double this year.

Mostly Graham grows dulse, the red, leathery-leafed up-and-coming star of the seaweed market right now. Most of the dulse currently available is harvested from the wild and sold dried.

Inside one of the buildings on Graham’s 12,000-square-foot lot, dulse grows in three large tanks. Above them shine the red and blue rays of LED grow lights, more commonly used on the marijuana farms farther up the coast.

Seven more tanks of dulse grow outside, under the gray Monterey Bay sky. The indoor dulse, however, is growing much faster. And this is changing more than their harvest rate. Over generations, this dulse will adapt to the constant light and faster growth. And these adaptations are making them look, feel, and taste different than the outdoor dulse, with bigger, thicker, meatier leaves.

“It’s a lot like heirloom tomatoes,” says Graham. “It’s the same exact species, but it’s different.” Generations of breeding and growing experiments are starting to produce an expanding diversity of seaweeds.

Seaweeds that chefs are excited about.

02

Rebranding the Weeds

But for many Americans, seaweed is still just, you know, seaweed—the same slimy, stringy fronds lying on the beach covered in flies. And besides wrapping it around sushi and snacking on fried nori chips, what can you really do with it?

A new wave of seaweed farmers, chefs, and advocates has some ideas. The first step: rebranding the weeds.

Emily Stengel prefers to call them sea greens or sea vegetables.

Stengel is deputy director of the aquaculture farm/research group/community development nonprofit GreenWave, which heads a collection of farms growing sugar kelp in the Long Island Sound off Branford, Connecticut. She says the kelp, native to those waters, has more iron than red meat, more calcium than milk, and a long roster of beneficial minerals and fatty acids.

“A lot of the great minerals that you get from fish actually come from [the fish] eating seaweed,” she says.

More analysis is needed, but dulse—and most other seaweeds—can also be rich in vitamin B12, amino acids (like glutamic acid), iodine, potassium, trace minerals like iron, zinc, and copper, and fatty acids like omega-3s.

Eating seaweed isn’t new. Coastal cultures have always incorporated it into their diets, though today we think mainly of Japanese foods—especially purple laver, also known as nori—and sometimes Welsh, Irish, or Norwegian cuisines.

Americans have been slow to add seaweed to their diets, but we’re already eating more seaweed than we know, as a more subtle ingredient. A substance called carrageenan has long been extracted from seaweeds for use as a thickener or gelatin substitute and is commonly used in everything from ice cream to toothpaste to Fruit Gushers.

And we’re slowly coming around to more seaweed-forward foods. Roasted nori snacks, for instance, have exploded in popularity in recent years. New farming techniques and varieties specific to the United States—most of that nori is farmed in Asia—could increase seaweed’s popularity and extend it beyond the snack and sushi worlds.

But that’s not all.

03

Tastes Like Bacon

Chris Langdon just wanted abalone to grow faster. It takes about three years for most farm-raised abalone to reach market size. More nutritious food than the wild-harvested kelp they typically eat could be a way to cut down that time. So after years of breeding and experimenting, Langdon came up with a strain of dulse for the abalone farms he works with in Hawaii that grows faster than usual and, since it can be grown in tanks, isn’t subject to seasonal changes in quality.

But a colleague at Oregon State University, where Langdon researches shellfish aquaculture, envisioned a broader use for the new strain of seaweed. Chuck Toombs, an instructor at OSU’s business school, suggested looking into how the new strain could be marketed to people, not just giant shellfish.

The marketing wasn’t too difficult to come up with. Dulse is about 20 percent protein by dry weight. “The steak of the seaweed world, if you like, in that respect,” says Langdon. (Beef jerky contains around 33 percent protein.)

And it tastes a bit like bacon when fried.

The announcement, in 2015, that Langdon’s team had developed a strain of seaweed that could taste like bacon got a lot of press. Langdon felt a bit awkward about that. He says he worried they’d gone out on a limb with the claim.

“Then we got angry emails from vegetarians saying they had been eating dulse since they were kids as a bacon substitute in dishes like DLTs,” says Langdon. “That was music to our ears—nice to hear confirmation from outside sources.”

They hired a research chef, Jason Ball, formerly a research intern at the Nordic Food Lab, and tried to figure out what else they could make with their new vegetable. Those experiments included using it as a salt replacement in sourdough (giving the finished loaves a hint of umami), as a replacement for aroma hops in beer (slightly briny, but not highly noticeable), and just as itself in a salad, ramen, and seafood sausages.

I fried up some of Graham’s dulse at home, just to see. It turned from red to green as soon as it hit the oil—and shot slimy green droplets onto the stovetop. The pieces I fried with bacon fat tasted, not surprisingly, more like bacon, but the ones I fried in vegetable oil were crispier and tastier—more like a kale chip than bacon, but with enough saltiness that the comparison wasn’t unreasonable.

“Just like pork belly, you have to do things to it—cure it, smoke it—to get to that bacon taste,” explains Ball.

GreenWave’s Stengel says she could see seaweed in the center of our plates, as a meat substitute, “though I don’t think it necessarily has to be in the form of fake meat.” But mostly she wants people “to think of sea greens as a vegetable, not just an accoutrement, as it has traditionally been in Asian cultures.”

Graham, purveyor of small quantities of labor-intensive seaweeds, can’t imagine them in the center of our plates. “You just can’t eat a cup of seaweed like a cup of broccoli. That’s just a lot, man.”

He thinks of seaweed more like arugula or radicchio. Or truffles, he adds. “You don’t eat a pile of truffles. Small amounts go a long way.”

Graham does see a future in using seaweed as an ingredient in food products like kelp noodles or snack chips.

“I am optimistic that food scientists are going to do some awesome things with seaweed,” he says.

Chef Vitaly Paley, who runs four restaurants in Portland, Oregon, has had Langdon’s dulse on the menu in several dishes for the past couple of years. But he’s still easing his customers into it. “We’re not a seaweed-eating culture in America, at least not yet, and so we have to put it in familiar surroundings for now,” he says. “If I put it next to tuna, all of sudden they’ll eat the seaweed. But if I lay out a plate of seaweed with dressing, they might not.”

Chef Matthew Varga of Gracie’s in Providence, Rhode Island, uses sugar kelp from the seaweed operation out of Walrus and Carpenter Oysters. “I think you’re going to see a lot more of seaweed on menus,” he said. “Especially here in Rhode Island, because it’s a new crop that’s readily available. Accessibility is everything, especially with seasonal ingredients.” Varga uses fresh, frozen, and dried seaweeds—often kelp. He recently dredged sugar kelp in lobster beurre monté, served it with steak, and finished it with a kelp-infused sea salt. “Here in the States it takes a little work around, but if you match seaweed with familiar textures and flavors, diners can associate with it far better.”

04

A Larger Role for Seaweed

But the benefits of producing seaweed go beyond taste and nutrition. Growing seaweeds requires no fresh water or other inputs—just sunlight, seawater, and the minerals it already contains. Compared with terrestrial crops, they require very little space and grow exceptionally quickly.

And when it comes to ocean farming, there is an additional benefit. Like oysters and mussels, seaweeds clean the water as they grow. That means absorbing excess nutrients that drain into coastal waters, which can contribute to algal blooms and the resulting low-oxygen “dead zones” that occur once those algae die off. And since seaweeds are ultimately just plants, they take up carbon dioxide, helping mitigate ocean acidification, at least on a local scale.

“Add to that from an economic perspective,” says Jules Opton-Himmel, founder and owner of Walrus and Carpenter Oysters in Narragansett, Rhode Island, which branched out into sugar kelp farming in the Narragansett Bay in 2015. “We are usually working on oysters in the summertime, and then it closes in winter. So this allows us to keep full-time employees. It opens up more opportunity for them.”

Seaweed farmers and innovative chefs see a bigger market and a bigger role for seaweed in our diets. Some of them envision a network of small-scale seaweed farms just outside major cities—floating in the water column, absorbing excess nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon dioxide and turning it into clean protein for Seattleites, New Yorkers, and Los Angelenos.

Big picture, Mark Bomford, director of the Yale Sustainable Food Project, is skeptical that seaweed will be the savior for a booming, protein-hungry population. “I think we’ll see growth in seaweeds as part of more diversified production in general and as part of economic diversification in communities where fisheries have declined, but I don’t view seaweeds as supplanting agricultural staples for food security any time prior to a global population peak and plateau or decline.”

On a small scale, though, Graham could see closed aquaponic systems in which oysters and seaweed absorb the waste produced by fish. Or seaweed growing as an aid to shellfish farms, helping mitigate the acidification caused by excess CO2 in the water, which limits the dissolved calcium carbonate that oysters and other shellfish need to grow. Or tanks of seaweed in restaurants, ready for the picking. (Currently, the seaweed he distributes lives in a bag of seawater in the fridge, where it lasts for a week—“so when the chef takes it out of the bag, it’s still alive, as if they have a windowsill herb garden.”)

OSU’s Langdon is looking forward to experimenting with different growing conditions to manipulate protein levels or trace minerals in the seaweed or to produce different textures based on what you want to do with it in the kitchen—one of the benefits of onshore small-scale experimental farms like Langdon’s.

“We know how to grow roses and wheat, but with dulse, we’re still at the early stages of learning,” says Langdon. “It’s only in the past year and half that we’ve been able to grow what I’d call high-quality dulse.”

“There’s a lot of potential in seaweed, and I think it will play a larger role in supplying food, fiber, fuel, fertilizer in the future than it does today,” says Bomford. “Our staple terrestrial crops, however, do have an R and D head start of about 15,000 years or so.”

05

Grow Your Own

The vast majority of seaweed currently produced in the United States is harvested from the wild, but some species, like sea lettuce, are prone to booms and busts, making sourcing them unpredictable, and others, like ogo, are found only in tough-to-access habitats like mud flats, making them hard to harvest and tough to clean.

Wild harvesting is also limited to low tides, and for many species, it is limited to the spring or summer months—limitations that can keep prices high. But seaweed farming opens up new options.

And what does it take to grow your own? Seaweed begins as free-floating spores. For GreenWave, those spores are bred in a lab, attached to a long string and wrapped around a spool. That spool is attached to and unwound around a line anchored to the seafloor and held up by a buoy floating 6 to 7 feet below the surface of Long Island Sound.

In ideal conditions, the sugar kelp can grow several inches per day and go from sea to harvest in just a few months. For GreenWave, that harvest happens all at once, when the waters begin to warm in mid to late spring, after which the kelp is processed into fettuccini-width noodles, blanched, vacuum-sealed, frozen, and distributed to restaurants.

Like a wine’s terroir, the final product can vary based on the growing conditions, says Stengel. She calls it merroir and mentions a time they processed the same kelp species grown at farms in different places around the Long Island Sound, each absorbing different mixes of nutrients in different wave actions and light exposures depending on their locations. “Every single one tasted a little different—brinier, crunchier,” she says.

But ocean-farmed isn’t the only option. Unlike GreenWave’s man-made kelp forest off Connecticut, harvested by boat, Graham’s farm consists of tanks sitting on a concrete pad, fed by seawater piped in from Monterey Bay but otherwise separate from the ocean. Tank farming can give more freedom for harvest and experimentation. “If you can grow it, you can harvest at any time and at any quality,” says Langdon.

In this “tumble culture,” bubbles churn the tanks, circulating the clumps of seaweed so they all get a turn to absorb whatever light is filtering in.

In blue tubs in Graham’s facility, dulse is grown with varying levels of light and minerals and bubbles, with efforts to determine which conditions best eliminate a brown gunk that tends to grow on the leaves and has to be cleaned off by hand to make the leaves restaurant-level pretty.

In other tubs, green sea lettuce—“just like lettuce but with more protein”—bumps around. In another, ogo, a stringier, crunchier seaweed often used in poke, floats in shaggy clumps.

Graham takes a handful of red sea grapes out of one tank. They look just like their terrestrial namesake, only much tinier, and the pop between your teeth and the texture of their skin also recalls grapes, though they taste brinier. He only sends these out as special treats to loyal clients, for now.

In the next tank, an even more precious crop slithers in a slow, gentle flow of water and bubbles—a silky, fragile type of nori he acquired a month before, peeled off kelp in the bay’s vast kelp forests. He’s not sure what to do with it yet, whether it can be successful enough in a small tank for it to make sense to sell, but he’s excited about it. It’s a vision of the future of seaweed farming, of the possibility. He’s not telling his clients about this new experiment for now.

There are also two 1,000-gallon tanks, each about 12 feet tall, and filled with dulse. He says these tanks can grow one ton of highly nutritious food a year on an 8-by-8-foot footprint, a level of productivity that excites those concerned about how to feed a human population expected to approach 9.7 billion by the middle of this century.

And if seaweed is going to be a bigger component of our diets in the future, we might as well learn how to cook with it now.

06

Back to the Test Kitchen

[Ed note: After Matthew Berger delivered his seaweed story to the Cook’s Science team, Test Cook Sasha Marx began developing his own recipes for the home cook. The following is from his perspective.]

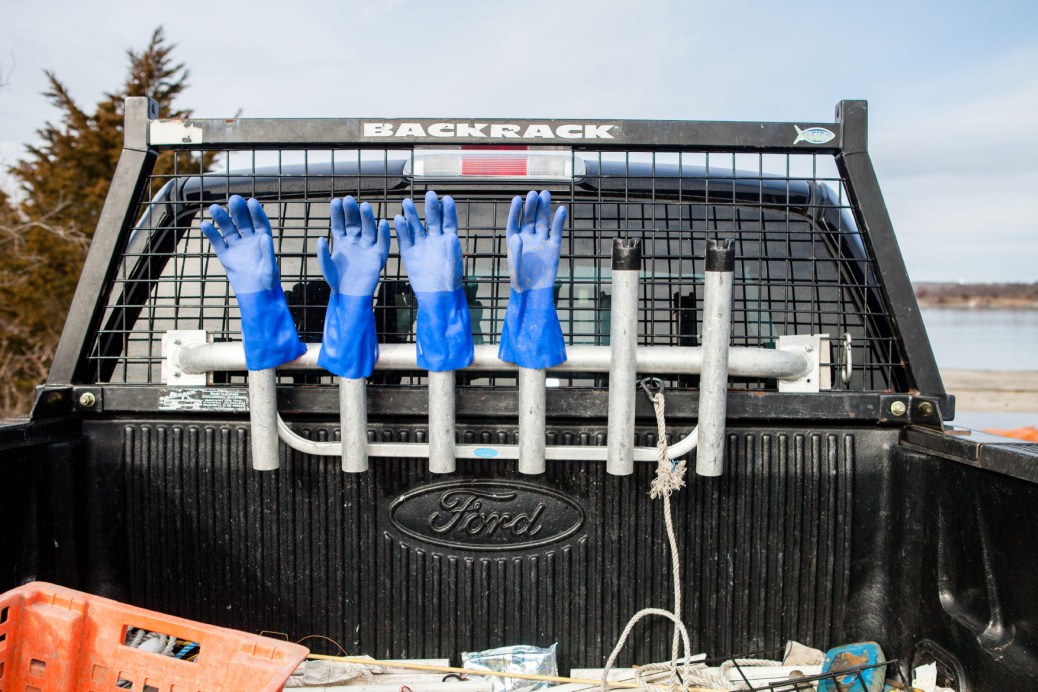

Early on a Tuesday morning in January, a few of us from Cook’s Science met the Walrus and Carpenter Oysters team at the foot of the Fort Getty Park boat ramp, in Jamestown, Rhode Island.

Walrus and Carpenter Oysters was founded by Jules Opton-Himmel in 2009, soon after he graduated from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. He started the company with 12 oyster cages and a little aluminum boat. “In the first year, I killed 90 percent of the oysters,” he told us, with a laugh. Business has since improved; today, they have two farms, four boats, and 1,500 cages and service more than 50 restaurants. In 2015, they decided to expand into seaweed (or “sea vegetables,” as Opton-Himmel says).

And we were there because Opton-Himmel had agreed to take us out on a boat to check out his newest venture and taste some of their young sugar kelp, which they officially call Cabbages and Kings Kelp. (The kelp had been incubated from spores in a hatchery back in the fall and transferred to the ocean six weeks later. The full harvest will take place this spring.) I had never (purposely) eaten seaweed straight from the water and was curious to try it. I was in search of inspiration for seaweed recipes for this story.

We climbed aboard the 21-foot fishing boat, along with Dave Bailey, an aquaculture technician from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who had helped the Walrus and Carpenter crew set up their hatchery and advised on both the tactics and timing of growing kelp in the ocean; Steven Medgyesy, who does communications for Walrus and Carpenter; and Clam Cake, a very well-behaved dog. We pushed off into Narragansett Bay.

“Why seaweed?” I asked, as we sped out to where the rope lines of sugar kelp, which are strung from buoy to buoy, were growing at three different levels beneath the sea—6 feet, 3 feet, and right at the surface—in an effort to determine which depth (and resulting access to both light and varying levels of nutrients) worked best.

“The fact is that it takes no feed, pesticides, herbicides, fresh water, to grow a food that’s high in all these essential minerals and elements,” said Opton-Himmel. “The way things are going with climate change, it may not be the next truffle, but it could be a staple food product. We can’t sustain ourselves the way we have been.”

And growing seaweed during the winter months would allow Walrus and Carpenter to remain open and operational year-round, he added, keeping full-time employees and opening up more opportunity.

When we arrived at the buoys, Opton-Himmel pulled up a rope of the sugar kelp. Because this harvest was so young, it was closer to a “sea-microgreen” than a full-grown sea vegetable. It grew light translucent green, hanging craggily off the twine.

Opton-Himmel cut some off the rope with a knife and gave me a handful. It wasn’t slimy at all, but crunchy, tasting slightly sweet and mildly briny, with a peppery finish reminiscent of watercress, arugula, or nasturtium. The kelp’s edges were rippled—all the better to modify water flow and access more nutrients—causing it to look almost like mafalde pasta. Maybe I should make a pasta dish, I immediately thought. Because the sugar kelp had this unexpected sweet edge to it, I also wondered if I could incorporate it into a sweet application. Seaweed panna cotta? Seaweed ice cream? Seaweed cake?

I asked if he had considered harvesting at this early stage in the growing cycle and marketing his crop to chefs as a specialty winter microgreen.

“Do you think chefs would go for that?” Opton-Himmel asked, somewhat skeptically.

“Hell yeah! I cooked in restaurants in Boston and Chicago, and I can’t even tell you how tired I would get of winter. Chefs who are trying to work with local ingredients in cold climates are so sick of looking at beets. It would be awesome to work with a green vegetable in the winter that wasn’t grown thousands of miles away or in a greenhouse.”

I was excited.

It started to snow as we finished tasting and began to head back toward shore. Our hoods pulled up over our heads, the winter wind whipping our faces—it was exactly what I had expected ocean farming during a New England winter to feel like. Before we climbed back into the car to thaw out our numbed appendages, Opton-Himmel gave us samples of both their fresh and dried sugar kelp to take back to the test kitchen.

Now the real work could begin.

I wanted to start working with the fresh seaweed from Walrus and Carpenter, but I knew that fresh sugar kelp wasn’t going to be easy to procure for the everyday home cook, so I also started looking into dried varieties of all kinds. Why are there so many dried kinds? It comes down to the simple fact that many types of seaweed are too tough or don’t taste great when fresh. “A few species can be eaten raw if they are completely fresh and collected from areas of clean water,” writes Mouritsen. “Most, however, need to be processed in some way, usually by drying, cooking, or toasting, in order to make them palatable. This often results in a noticeably improved flavor,” he continues.

I ordered a bevy: wakame, hijiki, kombu, ogo, dulse, and, of course, nori.

Interestingly, as foreign as eating seaweed may seem to many Americans, we do eat it (or some derivation of it) more frequently than you’d think. This is because some common gelling agents come from seaweeds: alginate, carrageenan, and agar. These long and unique polysaccharides bind water, turning liquids into more viscous and stable gels. They have been used for centuries in Asia and elsewhere, and today are frequently used in food products.

I decided to start work on two very different types of recipes—a sweet preparation and a savory one. My goals? I wanted to highlight the versatility of seaweed. And I wanted to create recipes that were surprising. No boring seaweed salad here. There was so much further I could go, flavor-wise, without making the recipes difficult or esoteric. I would start with familiar foods that people already loved and add the depth of flavor, beautiful color, and (of course) nutritional aspects of seaweed.

And what’s more beloved than pasta and ice cream?

For my pasta recipes, I started out trying to roll pieces of the fresh sugar kelp right into fresh egg dough, which is something I’ve done before with fresh herbs like parsley or chervil. It worked, but the kelp was too subtle in flavor to impart enough oomph to the pasta dough. So I started thinking about using ground dried seaweed. Dried nori (used for sushi rolls) packs a lot of toasty seaweed flavor and is a great entry point for people who haven’t worked a lot with seaweed. It’s easy to toast and grind into a fine powder. The powder itself is super versatile and can be used in a number of ways. We’ve used it before as a seasoning for chips, and here we added it to bread flour for an egg-based fresh pasta dough. The resulting pasta dough is a deep green color, and when rolled out and cut into pappardelle, it actually resembles pieces of fresh seaweed. (I also added the nori powder to butter to make a compound butter great for spreading on bread or basting on cooked fish and meat—check out the recipe, below.)

In the end, I developed two different recipes to pair with the pasta. I started by trying to create a riff on spaghetti alle vongole. But one taste of the first attempt and I knew: the garlic and chile were too aggressive. They completely overwhelmed the seaweed flavor in the pasta. Given that the point of the recipe is to highlight seaweed’s flavor, I needed to pair the pasta with something more delicate. What about . . . mussels? I steamed them with white wine, shallots, and garlic, took them out of the pan, and removed them from their shells. I used the liquid left in the pan to make a briny, delicate butter pan sauce. Tossed with the seaweed pasta and fresh tarragon, it made for a simple and delicious dish.

For the second pasta, I wanted to focus more on the glutamate properties of seaweed—the deep umami flavor in seaweed also pops up in ingredients like tomatoes and cheese, which thus seemed like natural pairings. (Umami was, in fact, first discovered in seaweed.) I blistered cherry tomatoes in a hot skillet, then marinated them quickly with extra-virgin olive oil and smoked paprika before tossing in the cooked pasta and finishing with sherry vinegar, a little fish sauce, chives, and some Pecorino Romano. The ultimate glutamate bomb of a dish—and a beautiful one, to boot.

On to ice cream.

While working as sous chef at Parachute in Chicago, I had made a kelp ice cream. While it sounds a little odd, seaweed brings a subtle savory note to dessert when steeped in a neutral sweet cream ice cream base, producing an interesting, hard-to-pinpoint flavor (think: green tea ice cream).

I started with the ice cream base that Dan developed after attending the Penn State Ice Cream Short Course (remember that?) and tested it with a number of different seaweeds—kombu, hijiki, wakame, and the fresh young sugar kelp. And I’ve got to say, the ice cream with the sugar kelp was amazing. It brought a nice subtle brine to the ice cream without an overpowering seaweed flavor. I’m not sure I would have wanted to eat the ice cream while out on the boat in the snow, but it was good nonetheless.

Because not everyone can go seaweed farming before making their winter batch of ice cream, however, I knew I needed to create a replicable flavor with a dried seaweed. Wakame was too intensely vegetal on its own. Kombu brought smooth, deep umami that we liked, and hijiki made a brighter and sweeter ice cream. In the end, a combination of kombu and hijiki gave us an ice cream that was not in your face with seaweed flavor. If you didn’t know it was a seaweed ice cream, it would be hard to pin down what, exactly, you were tasting. (It’s how I like to use smoke in food, too—as soon as you can really taste the smoke and it becomes an exercise in eating campfire, then you’ve gone too far.)

I am drawn to that elusive quality of seaweed. Like wine, seaweed is very difficult to describe with tasting notes without falling into the trap of vague buzzwords. This added to the recipe-development challenge of finding a way to highlight an ingredient that usually does its work behind the scenes. Seaweed brings a lot to the table while defying categorization.

Field Photography by Kevin White.

Styled Food Photography by Steve Klise.

Food Styling by Marie Piraino.

Art Direction by Lindsey Chandler.

07