The first course was herbed white beans with grapefruit, blood orange and asparagus with heirloom carrot, sumac, pomegranate and 2 milligrams of THC. Then came hamachi and caviar alongside asparagus rolled in hemp seed; broccoli stalks with THC-infused habanero mousse and dandelion purée; and lamb Wellington anointed with a spice rub, mint pesto, and a THC-dosed lamb jus. Eight courses and 10 milligrams later, the guests had grown convivial, suit jackets slung over chairs, giggling as a live cellist played in the background. By the end, says chef Chris Sayegh, everyone was “euphoric.”

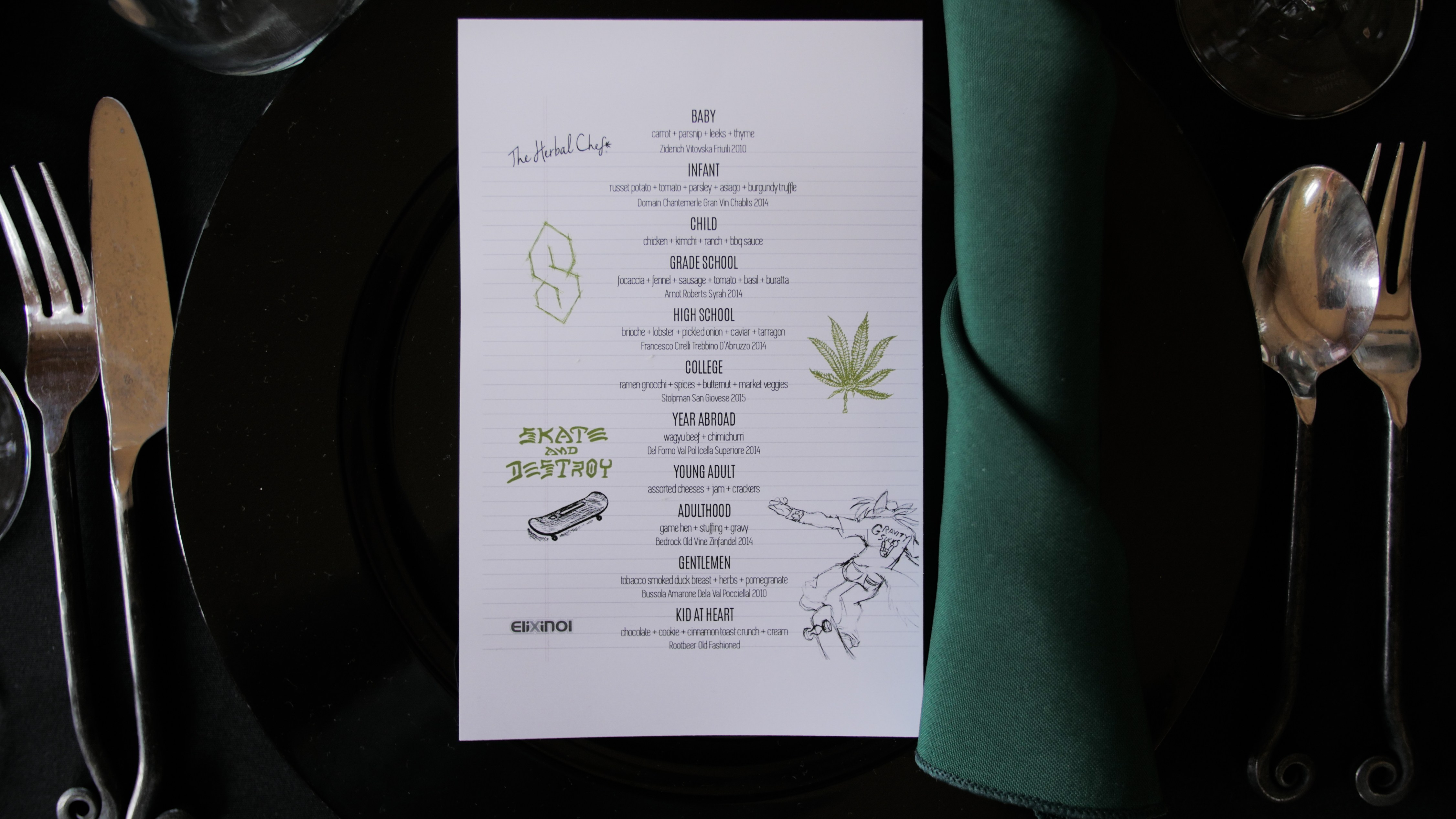

That’s a typical dinner event for Sayegh, known as The Herbal Chef. Sayegh, who artfully laces his dishes with THC like some might use hot peppers or fresh basil, routinely hosts such meals, with price tags in the hundreds, and he plans to open the nation’s first cannabis-themed restaurant by the end of 2017.

But tonight is a departure from his usual fare. He’s spent about a week creating a sprawling THC-infused landscape of jolly cookie-adorned houses, a towering Christmas tree, a fondant-encased UFO (complete with disgorged, Santa-hat-wearing space aliens), and fluffy bushes made of confectioners’-sugar-dusted cannabis nugs.

But no one will nibble on this intoxicating masterpiece.

Sayegh is at the forefront of a growing movement to reimagine cannabis in the kitchen, and he’s become known for his many-coursed gourmet THC-infused dinners in a style he describes as “French with Italian and Middle Eastern influence.” But tonight his gingerbread construction—which he’s created for a party benefitting the victims of a warehouse fire in Northern California—is just for show. Sayegh hasn’t lab-tested the village, so he doesn’t know how potent it might be, and he won’t serve imprecisely dosed food. Once upon a time, the menu included cannabis-infused appetizers to appease guests salivating over the off-limits village, but it turns out cocktails are on offer at this party, and mixing cannabis edibles with liquor can make for a “dizzy” experience, he says; he doesn’t serve them together. Guests still partake of his hors d’oeuvres, but they’re made solely from non-mind-expanding ingredients. Navigating such things are all part of the job; complications traditional chefs have never pondered.

Take all the problems an average chef has to deal with and throw in a psychoactive ingredient that requires some scientific chops, and you start to understand the quandary Sayegh and his ilk are facing: How do you create cannabis meals that are effective, responsible, and also delicious?

Sayegh wears chef’s whites. He’s quick to smile, athletic, with his hair cropped short on the sides and a tight burst of sandy curls on top. His Maltese-poodle mix, MooMoo, is cavorting around his feet. Just a few years ago, you wouldn’t have found him in uniform, but pondering his fate at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He was a sophomore studying molecular biology, homesick for the mansaf and other dishes his Jordanian family raised him on—and a fledgling pot smoker. A budding scientist, he decided that if he was going to get high, he should probably find out what it was doing to his body.

“Long story short, I started to research that and I had this epiphany,” says Sayegh. “I need to feed people proper nutrition from the earth and use plants as medicine.”

He dropped out of college and started his training in restaurants, logging time in Michelin-starred kitchens in New York and California while experimenting at home with cannabis. Entrepreneurial from the start, he trademarked the name “Herbal Chef” and started an Instagram account.

It was the Instagram account—where he posts things like artfully plated cannabis-infused foie gras custard with blackberry gelée, fish with radish marinated in a cannabis-vinegar blend, and peppercorn-crusted strip steak in a medicated Cabernet Sauvignon reduction—that led to his first private dinner. Things snowballed from there. Now, in addition to his restaurant ambitions and dinners, he’s gearing up for a TV show he describes as “Anthony Bourdain meets Bear Grylls.” The restaurant alone has presented a list of challenges not faced by traditional restaurateurs, from training cooks and waiters to work with cannabis to finding a landlord willing to rent to him.

There isn’t a playbook for someone who wants to build an empire around cannabis cookery. In his early days, around 2010, Sayegh noticed vexing variations in his recipes, depending on the temperature, time, and variety of his base ingredient.

“The taste was off; the potency was off,” he says. “And there was no research on, ‘Hey, if you heat cannabis up to this point, you’ll lose potency.’”

You can’t take a Le Cordon Bleu class in THC or crib from Julia Child or Thomas Keller. Due to federal regulations, it’s tough for medical researchers to investigate cannabis, let alone food science or culinary programs. Chefs working with cannabis are literally writing their own cookbooks and becoming amateur scientists in search of the perfect high enrobed in the perfect meal.

POT ENTERS THE LAB

“Herb” isn’t just cute shorthand for cannabis; cannabis is actually a flowering herb. The plant is indigenous to temperate and tropical parts of the globe, and archaeologists have uncovered proof that humans have been ingesting it in some form since prehistory. We like to smoke it and eat it, for ritual and medical reasons and just to have fun.

Chefs work with cannabis for lots of reasons, including a passion for its therapeutic properties, a love for the plant’s psychoactive effects, and the challenge of working with an ingredient that is only beginning to find its way into a fine-dining setting.

Because cooks use cannabis for its chemical effects, not just as a seasoning, a field of homespun, and increasingly more professional, technology has grown around it. Techniques for refining the plant matter into usable and potent ingredients range from stovetop simple to serious industrial processing—all in the quest to make bioavailable, accurately dosed dishes that also taste good.

Alice B. Toklas, who presided over literary salons in early twentieth-century Paris with partner Gertrude Stein, firmly ensconced the practice of cooking and eating cannabis in the cultural imagination with The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book. First published in 1954, it offered up a recipe for Hashish Fudge, which “anyone could whip up on a rainy day.” In addition to pulverizing a “bunch of cannabis sativa,” the recipe calls for black peppercorns, dried figs, and peanuts. In an introduction to the 1984 reprint of the book, food writer M.F.K. Fisher wrote that she had never tried one of the fudge brownies, but “am told they taste slightly bitter.” These days, no cannabis chef worth their herb would recommend throwing raw product into baked goods, but brownies can be an ideal vehicle for THC. It just takes a few more steps than Toklas imagined.

You could eat a pound of raw cannabis and not get high. That’s because the main functional ingredient in a cannabis bud is in the form of a compound called tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, or THCA. THCA has no psychoactive effect. But delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, does. Applying heat to THCA kicks off a process called decarboxylation, which transforms it into THC. When cannabis is smoked, THCA converts to THC along the way, and the process is largely taken for granted. Basically, every pot smoker, from a cancer patient to a teenage toker, embarks on an act of chemistry when they flick the lighter. But if you want to eat it instead of smoke it, things get more complicated. The most common way people decarboxylate, or “decarb,” cannabis for cooking is by toasting it on low heat (240 degrees Fahrenheit/116 degrees Celsius is a commonly recommended temperature) in an oven.

Elise McDonough, edibles editor for High Times and author of The Official High Times Cannabis Cookbook, has become a kind of cannabis test-kitchen guru over the years, running experiments and lab testing the results.

The main concerns when decarbing, according to McDonough, are burning the cannabis or toasting it too long at too high a temperature. She recommends checking on it frequently and stirring it up if it gets too brown around the edges. The THC will evaporate at 392 degrees Fahrenheit/200 degrees Celsius, and at higher temps the THC starts converting to cannabinol, or CBN, a cannabinoid known for making people sleepy.

The overeager may wonder if they can just munch on the toasted bud—the answer is yes, but it’s kind of a waste.

“It’s been decarboxylated enough that you would feel it but not with the intensity and extent that you would if you mixed it into a fat and then ate it,” says McDonough. “Because the fat is really helping it be absorbed into your body.”

THC is fat-soluble, which is why once it’s decarbed, cooks often infuse it into a butter or an oil, simmering it for hours on a stove or in a slow cooker and then straining it to produce a rich brew that reliably delivers THC to the bloodstream and liver. (Hence all those decadent brownies.)

Decarboxylated cannabis can (and has been) infused into a spectrum of household ingredients, from avocado oil to bacon fat, although some may be better conduits than others. In a trial where she infused and tested a number of vehicles, McDonough found that clarified butter and coconut oil produced especially potent solutions. Her hypothesis as to why? Saturated fats like butter and coconut oil are better able to absorb THC than monounsaturated fats like olive oil. “We’ll need to do more study,” she writes, “but in the meantime, all of you cannabis cooks at home can rest assured that using clarified butter or coconut oil for your cannabis infusions will result in a potent and cost-effective infusion.”

Old-fashioned “cannabutter” is a staple, but chefs have been experimenting with new methods over the years.

Seattle chef Ricky Flickenger got his start at a popular cupcake shop and now teaches home cooking classes—which included one on the science of cooking with cannabis, until shifting laws made him retire that particular session. A self-taught chef, Flickenger is used to figuring things out on his own and, like many cooks in the cannabis field, keeps up to date on scientific research. He’s partial to making his butters and oils with a product called kief, a powdery substance made from the glittery, hairlike trichomes that protrude from the cannabis plant. Kief is one of the many cannabis extracts that have found their way into dispensaries alongside traditional buds.

Extracts, or concentrates, are exactly what they sound like—products with high levels of THC that are made from cannabis by a number of methods, from sifting buds to isolate cannabinoid-rich trichomes,to supercritical CO₂ extraction, which uses carbon dioxide at very high pressures to pull cannabinoids from the plant. (This professional technique is a popular way to decaffeinate coffee.) There is a dizzying array of extracts available, as well as ways to consume them, from vaporizing to smoking them atop traditional bud. And some have found their way into the kitchen.

Chris Yang, a Los Angeles-based chef, brought his background in biochemistry to bear on his cannabis-infused dinners under the banner PopCultivate. Disillusioned with the business side of medicine, he dropped out of a graduate course in hospital management and found his way to cannabis chefery.

Yang extracts his own concentrates and then puts those in a rotary evaporator, or “rotavap,” a tool found in chemistry labs as well as molecular gastronomy kitchens. The rotavap uses vacuum to remove solvents from the concentrate, leaving Yang with a powder or resin that can be added to oil, butter, or glycerin.

“Which is amazing,” he says, “because then I can measure dosing by how many drops I’m putting in the food, not how many teaspoons of butter or tablespoons of butter. It’s very limiting if the proper dosing for food is you need two tablespoons of butter for one dose— it’s kind of hard to feed someone two tablespoons of butter.”

Yang prefers making his own extracts so he can personally tailor his product, isolating individual cannabinoids using a method called silica column separation. Then he can adjust the ratios of cannabinoids for a desired high.

FROM BUTTER TO TERPENES

When Sayegh, aka The Herbal Chef, first started messing around with cannabis in the kitchen, he made butters like everyone else, and drew on his science education to track his results.

“I started to take notes and write stuff down and pay attention to how much bud I was putting in the butter, how long I was steeping it for, what temperature it was at, and then I just started to build upon my own trials,” he says.

But butter wasn’t where he wanted to stay. He wanted to make savory dishes, not batches of brownies. (“Brownie” has become a kind of catchall code word, spoken ruefully by chefs who want diners to think outside the limited vision of infused food.)

Now, Sayegh works with lab-produced extracts. Though they’re mostly fat-soluble, he says the lab he works with also produces a water-soluble version using a proprietary method. He’s tight-lipped about exactly how the water-soluble extract works, but says it “helps keep the integrity” of the THC “without burning it off,” and means he can infuse frozen meals that can withstand the oven and microwave—something he does especially for critically ill patients, in collaboration with a nutritionist.

Sayegh has experimented with infusing foods via tabletop vaporizers—machines that vaporize cannabis for inhalation. He traps the vapor in an oven bag with poultry or fish and then ties it off and pops it in the oven.

“It doesn’t get you high, but it infuses the terpene and the aromatics into the skin,” he says. “Which gives it this whole new complexity.”

He’s also used vaporizers to infuse beef tartare, similar to smoking it, and even conducts terpene wine pairings.

Yang has tried drying and dehydrating cannabis leaves and using them like dried basil or oregano. It didn’t quite work out. Unlike traditional herbs, Yang says the dried cannabis didn’t retain enough aromatics to make it a prominent flavor in the dish.

But all this invention is for naught if the food doesn’t taste right, and plenty of people are leery of the piney, grassy flavor associated with cannabis-enhanced food.

Many chefs have come up with ways to curtail the vegetal tang that so many find overwhelming. Yang says hot foods hide the flavor better than cold, as do foods with high sugar content, like juices. One popular cannabis gourmand, who goes by the moniker JeffThe420Chef, advocates soaking and blanching cannabis to rid it of things like chlorophyll, the green pigment vital for photosynthesis that is also responsible for a lot of the plant’s grassy taste. Sayegh says he has become accustomed to masking the flavor, bringing it into a balance with everything else in the dish so that diners won’t taste it unless he wants them to.

Meanwhile, some are embracing one particular set of compounds that give cannabis its multifaceted flavor: terpenes.

Terpenes are aroma and flavor compounds found in all kinds of plant foods, such as cinnamon, oregano, and lemons. Cannabis shares certain terpenes with mangoes, black pepper, and rosemary, and different strains of cannabis have different terpenes. It’s not unusual for cannabis sold in dispensaries to come with tasting notes, like a glass of wine, and a company in Amsterdam even has a detailed “flavor wheel” of available strains with flavors as specific as “Tabasco” and “bread fruit.” Sayegh and others believe terpenes, like cannabinoids, shape the high and have therapeutic benefits—from calming to euphoric—and will pick and choose strains based on that. Some studies have supported this direct connection between flavor and effect, but, as with many aspects of cannabis, research has been limited by the plant’s legal status.

Melissa Parks, a classically trained chef who once worked in research and development for General Mills, is now the executive chef of Las Vegas-based edibles company Vert. She once orchestrated a dinner where she paired tokes of cannabis with dishes that complemented their terpenes. She married a particularly earthy strain called Bio-Diesel (“It had smells of when you drive into a forest over dirt with pine needles”) with a cocoa- and coffee-crusted pork tenderloin in sour cherry beurre blanc.

“With the addition of these terpenes, whatever is lingering in that beautiful essence of plant matter that has hit your palate illuminates something in a dish you would have completely ignored or never seen,” she says. “It’s so fun!”

Of course, flavor and presentation are wasted if the diner leaves their meal having embarked on a trip they didn’t plan on taking.

“That is what is going to hold our entire industry back if we don’t do this right: the potency of edibles,” says Sayegh. “Everybody and their mother’s had a bad experience. Because it’s like, ‘Oh, this little cookie?’ And then they eat it, and they’re throwing their brains up.”

TOO HIGH

The effects and duration of cannabis differ depending on how you take it. When you smoke pot, it passes very quickly from the lungs to the bloodstream. There is a rapid spike in THC in the blood minutes after inhalation, which declines after about an hour. But when you eat or drink it, it passes through your stomach and intestines to the bloodstream before entering the liver, where it’s metabolized and then spit back out into the bloodstream. This all takes time, which means that when you eat THC, it can sometimes take more than two hours to feel the effect—one that can last longer than from smoking, as the THC is gradually absorbed over hours by the gut, liver, and so on. So, while the experience is different from person to person, it’s safe to say that when you eat cannabis, it will take longer to feel the effect and that that effect can last longer than when smoking it. The lag time can also lead to overindulging.

When a person eats a marijuana-laced edible, “they may not feel anything for a while,” says Dr. Igor Grant, director of the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research at the University of California, San Diego. “And if they were doing it medicinally, they may say, ‘Well, maybe I didn’t have enough,’ and take some more, and then two hours later they’re very, very stoned.”

“It’s the bus that won’t let you get off,” says a filmmaker in San Francisco who preferred not to be named. He overmedicated on a batch of homemade cannabutter cookies and ended up desperately thirsty, hallucinating, and just way too high for about eight hours. He recalled the ordeal of waiting at a pedestrian crosswalk.

“It could have been 30 seconds, it could have been an eternity,” he says.

Such are the added challenges of cooking with (and partaking of) a psychoactive ingredient.

Chef Andrea Drummer, owner of Los Angeles-based cannabis catering company Elevation VIP, had her own version of that experience. The first drugged dish she ever ate was bruschetta prepared with infused olive oil, which she recalls with evident glee.

“Oh, it was so good,” she says. “So good. I kept eating them.”

Seven pieces was not a good idea, says the former nonprofit worker, laughing. She’s come a long way since then, and says the ability to calculate dosage through lab testing is one of the biggest changes in the industry. Prior to laboratory testing, attempting to determine the potency of an edible required guesswork, which could lead to unpredictable results.

“Understanding the levels of THC in the product” is essential, says Drummer: “making sure that translates into a great dining experience, that the guest doesn’t feel uncomfortable, or overwhelmed, or that they’re going to die.”

Drummer, like many cannabis chefs, works closely with a trusted supplier that tests its products for potency in labs. Once she creates a butter or an oil, she then has that product tested. Finally, diners are presented with menus that describe the dosage of each dish. She tries to keep four-course menus at “well under” 60 milligrams of THC, spread out over a leisurely meal so that diners can indulge. For comparison, “legal state” Colorado considers 10 milligrams to be a single dose. The effect of a single dose varies from person to person, and from smoking to eating.

“I would equate 10 milligrams to maybe a cocktail or a glass of wine,” says McDonough of High Times. For those with zero cannabis experience, McDonough suggests starting out with just five.

For home cooks, figuring out dosing can still be tricky.

“It depends on if you’re in a state where you can legally access it, or if you’re in a prohibition state,” says McDonough. Most cookbooks and guides provide a way to evaluate the quality of your cannabis and give it a ballpark THC percentage, which will help the home cook calculate it. “It’s better than nothing, but it’s still not very precise,” she says.

In a legal state, home cooks have access not only to lab-tested fresh product but sometimes also to lab-tested butters and oils. Some who prefer to infuse at home rely on online potency calculators, of which there are several. Sites like Wikileaf catalog the potency of different strains, and home potency-testing tools are starting to hit the market.

Still, the fear of overmedicating makes many nervous. There are no recorded deaths from overdosing on cannabis, but the effects of taking too much can be very unpleasant.

Michael, an event planner in San Francisco, used a potent homemade cannabis-infused coconut oil to fry egg sandwiches for himself and his wife.

“Both of us ended up spending the entire day paranoid, in fetal positions on the couch, watching like eight episodes of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos,” he says. It took about a day and a half for the effects to wear off.

Corinne Tobias, a home cook who writes about cooking with cannabis on her blog Wake + Bake, described an experience in which she ate half of an infused grilled cheese sandwich and got “super crazy ridiculously messed up.” She wrote that she felt like she was “melting into the floor” and spent “half of her afternoon” asking for reassurance that she was not dying. “When I first started cooking with cannabis,” she writes, “I had no idea that it was going to be such a struggle to predict the perfect dosage. I’d make oil using the same method, but every time I harvested a different strain, my cannabis oil would be stronger or weaker and I had to spend a day or two as a human guinea pig, slowly testing my oil until I knew it was just right.” Now she is a fan of the tCheck, a $299 home potency tester.

Home cooks fear cannabis the same way they fear making a soufflé, says Parks, who coauthored a cookbook, Herb, in part to help acclimate home cooks to the ingredient. She recommends doing your homework; Parks took college chemistry classes and drew on the expertise of her physician father to supplement her culinary training.

For newbie home cooks, she advises going for quality over bargains.

“If you’re going to cook with a wine, you want to be able to drink it by the glass,” she says. “It’s the same type of thing—if you’re going to be cooking with a strain of cannabis, you want to smoke it and enjoy that flavor and enjoy that high.”

Parks also urges home cooks to rely on people in the know for information: “I guarantee someone in that dispensary has made an edible. Ask them what they’ve done. Don’t be afraid to ask more than one person; the more people the better.”

Finally, she says, start slow. Try low doses, wait several hours—or even a day—to gauge the effect, and once you feel comfortable, slowly increase your dose by low levels. But, she says, don’t be scared.

“Embrace it for what it is,” says Parks, who keeps cannabis in her kitchen. “It’s an herb.”

THE NEXT BOOM

For chefs dealing with ever-shifting regulations and public attitudes, playing it safe is good business. That’s why there’s no one going Godzilla tonight on Sayegh’s gingerbread masterpiece.

In the kitchen, one medicated chocolate bar has been broken up into little pieces and placed in a bowl for people to dip into if they choose. It’s smooth and dark, with just a light grassy finish at the end—a far cry from Toklas’s herb-studded fig brownies.

Sayegh knows that THC in the kitchen has an image problem outside of the cannabis world. People dismiss it as a gimmick, something just for mega-stoners, or an opportunity to rip people off. Even Sayegh’s family balked at his career path. They weren’t thrilled when he dropped out of college. They were double un-thrilled when he remade himself as an infused-food gourmand. His mom booted him from the house and told him to stay away from his little brother. But even they’ve come around.

“My parents were a great introduction to the rest of the world, basically,” says Sayegh, who hopes that finely prepared food combined with the capacity to discuss the molecular structure of cannabis will help strip away the stigma of a plant still federally classified alongside heroin as a Schedule I drug. Far from a scourge, Sayegh and others see immense medical and economic potential in the herb.

Tonight, no one needs convincing. The people at this party, for the most part, are members of a younger generation that has embraced cannabis socially, medically, and in the kitchen.

When it comes time to unveil the gingerbread village, they crowd around, smiling and laughing, and whip out their cell phones to snap pictures—another delicious food photo for the Internet.

“It’s going to be the next tech boom,” says Sayegh. “It’s the opportunity of our lifetime.”

Header photograph by Henry Drayton, courtesy of The Herbal Chef.