It is a chilly February night in Kyoto, a bright red moon is rising against the black silhouette of Mt. Daimonji, and I am roaming a district of restaurants not far from one of the city’s most famous food destinations, the 400-year-old Nishiki Market. The street I am on features seductive sake bars and fancy sushi counters, but I walk on, toward a much more pedestrian spot, a 24-hour convenience store called Family Mart. It is a plain, glowing green and blue rectangle, its aisles filled with umbrellas, cat treats, and bean paste snacks.

I find what I’m looking for: a small prepared meal, which costs just 398 yen (about $3.50). It’s a simple meal, but for me it is extraordinarily special. It consists of a spike of green cucumber and a squiggle of yellow egg tucked into a sushi roll filled with white rice and wrapped by black seaweed; another roll features thin strips of pickled red cabbage. There are also three golden pouches of inari, or rice stuffed into a deep-fried tofu skin. The 24-hour convenience store—probably the last place most visitors to Kyoto would want to go for a meal—is exhibiting ancient Japanese aesthetic directives about culinary colors. This tenet of Japanese cuisine is so common across the culture that I am even able to find it at a place like Family Mart.

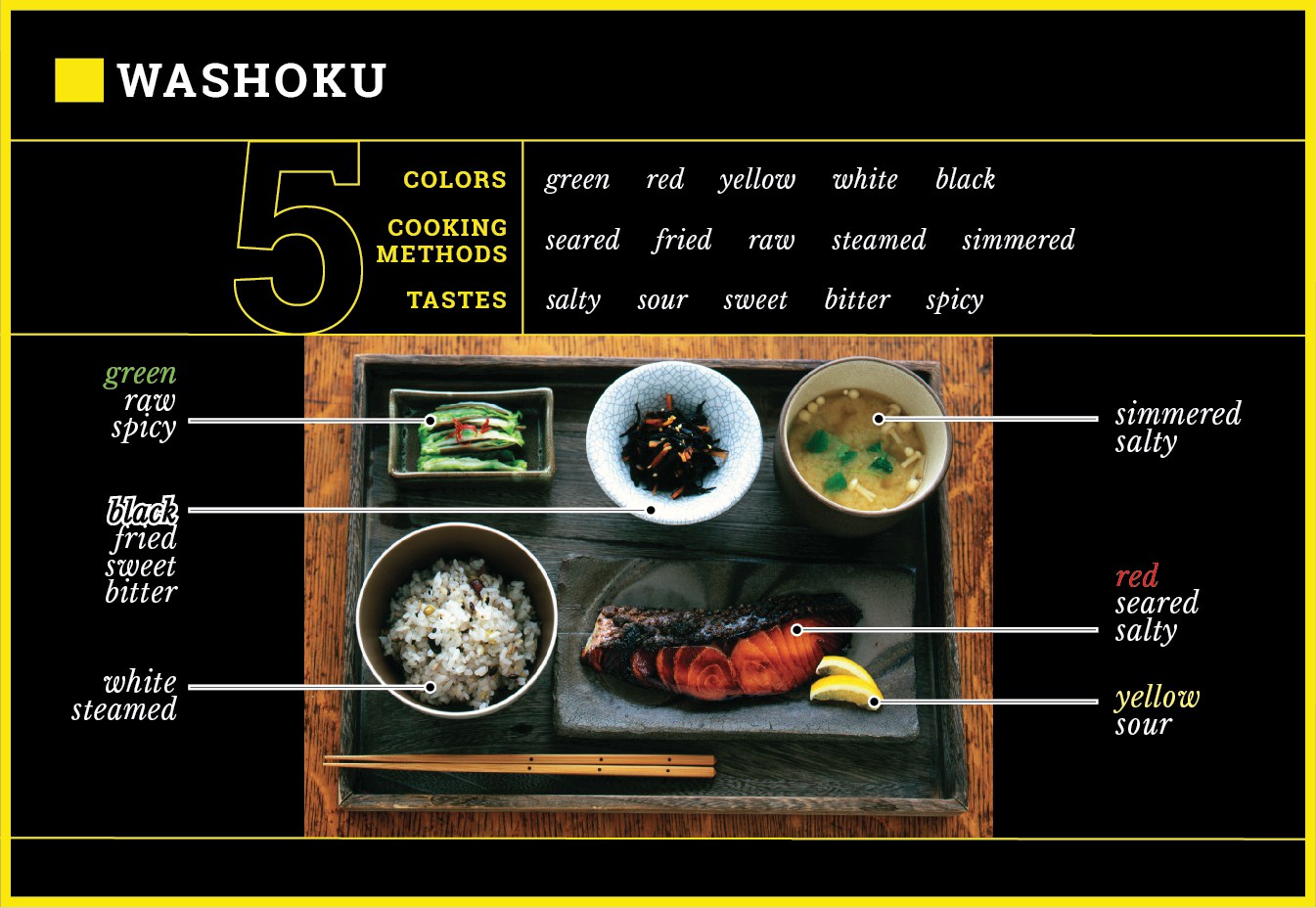

The attractive and intentional display of colors in Japanese cuisine is part of a larger set of food guidelines or ideals called washoku. “Washoku literally means the harmony of food, a way of thinking about what we eat and how it can nourish us,” Elizabeth Andoh, an authority on traditional Japanese cuisine, writes in her popular 2005 book, Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen. Like a set of Russian matryoshka dolls, even the precepts of washoku have an interlocking symmetry. There are five overarching principles of food preparation, and each principle contains five points.

For example, there are the five cooking methods: simmering, searing, steaming, frying, and leaving raw (not cooking at all). Every meal should contain one component prepared in each way. In the Family Mart meal, the tofu skin is fried, the rice is steamed, the seaweed and cucumber are raw, the egg has been seared or fried, the cabbage looked as if it had been simmered or braised. Each meal should also contain the five tastes—salty, sour, sweet, bitter, spicy—and the five human senses. Then there are the five outlooks, each having to do with the eater’s state of mind, such as respecting the work of those who toiled to prepare the food, coming to the dining table without ire, eating for spiritual as well as temporal well-being, doing good deeds worthy of receiving such a meal, and being serious in one’s struggle to attain enlightenment. And, finally, there are the five colors to be included in each meal: black, white, red, yellow, and green. The colors make a meal beautiful, but also have nutritional benefit. “Vitamins and minerals naturally come into balance with a colorful range of foods,” explains Andoh.

The five colors are also “a great tool for staying organized in the kitchen,” says Yukari Sakamoto, who works as a chef, sommelier, and Tokyo food guide and is author of the book Food Sake Tokyo. At first, keeping track of the colors may seem overwhelming, explained Sakamoto, but after awhile it becomes so routine that even a simple lunch can hit all five colors. “The rice is white. Black sesame seeds, nori, or eggplant will check off black,” she says. “Green is easy to check off, as there is broccoli, green beans, spinach, etc. Yellow is often tamagoyaki omelet, a hard-boiled egg, or yellow bell peppers. Red can be tomatoes, red bell peppers, or fruit like strawberries or cherries.”

The Five Principles traveled to Japan from China by way of the Korean peninsula about a thousand years ago, according to Andoh. Here the principles melded with the indigenous Japanese religion of Shinto, which holds a strong respect for nature and humanity’s connection to it. The five colors may be the most apparent element of the Five Principles, and while you can find evidence of this color theory across Japan, from the finest restaurants to food stalls on the street to convenience stores, that does not mean the Japanese are necessarily thinking much about the concept as they move through their days. “As with all aspects of culture,” said Andoh in an email message, “the people who actually practice their culture rarely articulate to others, nor even discuss among themselves, the theory behind their daily routines.”

For most Japanese, eating food that adheres to an ancient standard of color is just eating. While for many Americans, perhaps accustomed to a grain-heavy diet of yellows and browns, a meal that contains shades of white, red, green, yellow, and black is striking.

But that is not to say that Western food culture is ignorant of color.

“Colour is the single most important product-intrinsic sensory cue when it comes to setting people’s expectations regarding the likely taste and flavour of food and drink,” writes experimental psychologist Charles Spence, head of the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford, in his well-cited 2015 paper, “On the psychological impact of food colour,” published in the journal Flavour. If Japanese cuisine represents the beacon of food color practice, Spence may be the maestro of food color theory. His Flavour paper reviewed more than 150 research articles on food coloring and how it impacts the perception and behavior of eaters. His book Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating, which takes a look at how both flavor and our enjoyment of food are determined by all our senses, as well as mood and expectations, will be published in June. As Spence sees it, the color of food can significantly affect an eater’s expectations and thereby their actual eating experience.

Take what has become famously known as the 1973 Blue Steak study. The British researcher J. Wheatley invited dinner party guests to dine on a meal of steak, fries, and peas in a dimly lit room. Partway through the meal the lights were turned on to reveal that the peas were red, the potatoes were green, and the steak was blue. “A number of Wheatley’s guests suddenly felt ill,” writes Spence, “with several of them apparently heading straight for the bathroom.” In January 2017, Spence performed a miniature follow-up to Wheatley’s experiment at a North London restaurant for a British television show called Food Unwrapped. This time diners were served blue sushi. “They found it very difficult to eat,” says Spence.

Aversions to off-color meat and fish may be tapping into deeply rooted biologic responses, says Spence. For our ancestors, eating blue or green meat or fish could mean death. In fact, Spence hypothesizes that our predilection for colorful food may have developed as our species line grew more complex, developing eyes, for example, with three types of color-detecting cone cells—many primates have just two—which may have helped us to pick out bright fruit in a dark jungle canopy. The first intentional coloring of food occurred somewhere between 2,000 and 5,000 years ago, he says, when vintners intentionally left the skins of grapes in their mix, in order to give wines a rich red hue.

Spence agrees with Andoh that a colorful diet is likely to be a more nutritious diet, but also believes there may be a much more modern and banal reason behind our appreciation for a colorful meal. Humans “get bored,” says Spence, “if we have too much of the same sensory stimulation.” Food manufacturers are certainly aware of this, and color has become a grand culinary marketing tool; it can highlight the freshness or quality of the food and attract the consumer into buying it in the first place. In his 2015 Flavour paper, Spence mentions a 2001 study in the Journal of Food Products Marketing that reported that some 97 percent of the food brands displayed in grocery stores use food color to indicate flavor. More than ever, the science of food color appears to be making its way into the practice of food color.

“What is interesting is we are seeing chefs and scientists partner now more than ever,” said New York City-based culinary scientist Christopher Loss. “What scientists like Spence are trying to understand,” says Loss, “is what chefs have been doing for many thousands of years.”

Before leaving Japan, I eat one more colorful meal. I find it on the outskirts of Tokyo, at Haneda Airport’s International Terminal. The restaurant is called Hayakuzen, and its tag line is “The taste of beautiful Japanese cuisine.” My order sounds simple: salmon and salmon roe with rice. I am given a bowl of rice topped with a slice of salmon, the salmon roe, a dab of wasabi, a shiso leaf, and shreds of four different types of seaweed (white, red, green, and black), as well as a small green salad with pieces of pickled yellow daikon radish, among other little side dishes. I leave the country feeling happily full and full of color.

Styled food photography by Steve Klise.