The team at Cook’s Science (and everyone at America’s Test Kitchen, really) spends a lot of time eating—er—tasting different versions of recipes and commercial supermarket products, one after another. Palate cleansers are often touted as being helpful in situations like these. But is there any science to support their use? Isn’t sipping water effective enough to prepare your palate for that next dish, bite, or quaff? We spoke to experts—and conducted our own tests—to find some answers.

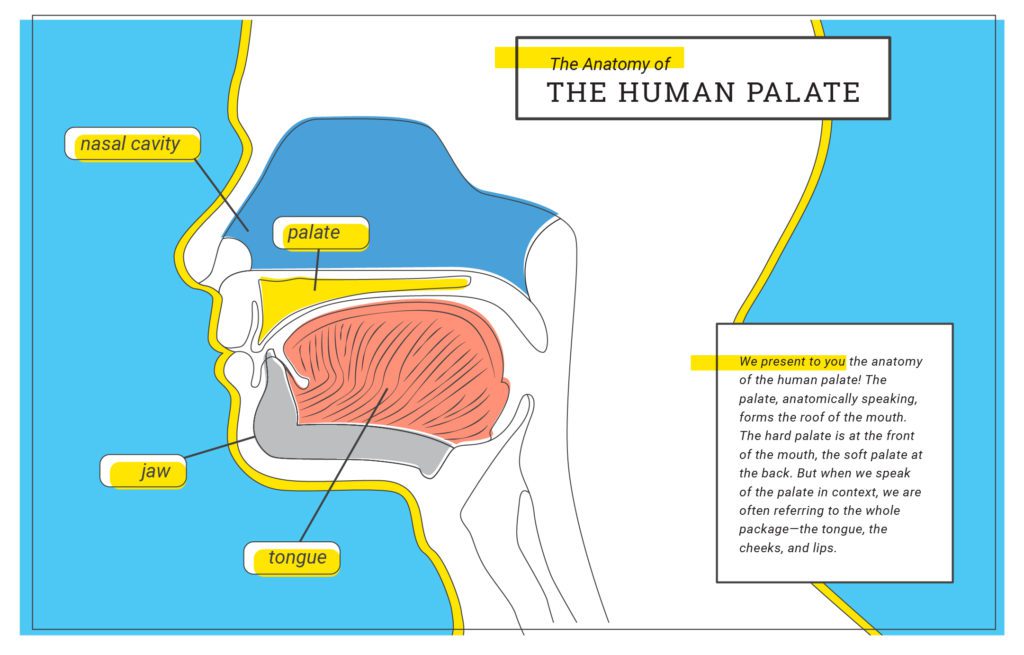

Before exploring the science, we needed a clear definition of the word “palate.” Is it a literal spot in your mouth? In part, yes. Anatomically, the palate forms the roof of the mouth. Though we don’t often think of it as a sensory organ, there are actually taste buds present on the palate. But in the context of palate cleansers, we define the palate a bit more broadly: as any and all parts of the mouth that contribute to our taste experience. Primarily the tongue, but also the lips, sides, roof, and back of the mouth.

And so what about the phrase “palate cleanser”? Generally, it serves as a catchall term for a variety of foods or drinks that people eat or sip to clear the mouth of the flavor of whatever they have just tasted. Others define a palate cleanser as something that stimulates the palate, therefore encouraging more eating. A palate cleanser could be a sip of water in between tastes of different wines, or it could be an entire minicourse unto itself. These minicourses are called intermezzi in Italian food culture and are intended to prepare the palate for the next dish. Fruit sorbet is common. In France, a traditional palate-cleansing practice during feasts is to take a sip of brandy between courses.

THE POWER OF TIME

While the thought of eating a particular food in order to help you eat more food certainly is fun, we were more interested in exploring if and how palate cleansers can help the taster make better judgments when performing side-by-side taste tests. To find out more about this issue, we approached a master. A master sommelier, that is.

We asked Scott Carney, Master Sommelier and Dean of Wine Studies at the International Culinary Center in New York, to give us his take on palate cleansers. Overall? Not a huge fan. “The object of palate cleansing is an attempt, however quasi-scientific, to create a clean slate on which the next evaluation is done or made,” he began. “I’ve heard bananas and olives, crackers and water, any number of things in individual circumstances to clean the slate and allow the next evaluation.” When he tastes wine, sometimes as many as 40 or 50 at a time, or teaches classes on wine, his goal is to be an “objective mechanism.” Physical palate cleansers do not often play a role in his work. Unless you consider time to be a palate cleanser: “I just try and give my palate a little rest. You inure to taste and smell over time. So you reset the palate over time. For me, it’s just taking a bit of a break.”

MAKE IT BLAND

Feeling slightly flummoxed that a master sommelier doesn’t rely on palate cleansers, we turned to the commercial food industry to seek out real-world palate-cleansing practitioners. Palate cleansers play a central role in sensory analysis studies conducted by major food companies. To learn more about the use of palate cleansers in the food industry, we asked Dr. Sarah Kemp, a food science consultant and former global head of sensory and consumer guidance at Cadbury Schweppes, her opinion on the matter. Kemp has helped design and lead many studies, such as one focused on the sensory characteristics of tomato sauces available in the United Kingdom market and exactly what qualities U.K. consumers desire. Kemp stressed that using a palate cleanser is critical to the success of these studies. “The aim of palate cleansers is to minimize carryover effects and adaptation from the previous sample.” In other words, palate cleansers are used “to reset the sensory system back to its base state.” The theory goes that by wiping the subject’s palate clean of the taste of the previous sample, palate cleansers prevent the tastes of samples from contaminating each other. The ideal in a sensory study is that if a subject were to taste the same sample at multiple points in a sensory test, that person would rate the sample identically each and every time.

To obtain reliable sensory data, food scientists seek out the best palate cleansers. And to determine the best palate cleansers, stand-alone studies have measured the efficacy of a wide variety of possible candidates. The results? Bland is best. The blandest of the bland, in fact. “Water at room temperature,” said Kemp. And not just any water. Water that is “as bland as possible, for example, distilled water or bottled water with minimal taste.”

In a 2009 paper from the journal Chemosensory Perception, researchers tested a variety of palate cleansers, including Table Water crackers, spring water, pectin solutions, whole milk, and warm water, in combination with a range of foods that each fell into different categories of taste sensations (from sweet, bitter, and fatty to astringent, hot and spicy, and minty and cooling). The only palate cleanser that was effective across all foods types was the cracker. Indeed, a literature search of recent food sensory studies published in peer-reviewed journals reveals that the most common palate cleanser in food sensory studies is a sip of water followed by a bite of unsalted crackers, such as unsalted saltines.

OPPOSITES ATTRACT

With this information in hand, we were left wondering if there was any research that suggested a mechanism through which palate cleansers could work. Is there any scientific basis to support the notion that palate cleansers affect taste perception in our mouth, or are we really just giving ourselves a mental break between tastes of flavorful foods?

One study, published in Current Biology in 2012 by Dr. Paul Breslin and co-workers—scientists affiliated with the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia—provides the beginnings of an answer. Breslin and co-workers explored the concept of drinking something with high astringency, like red wine, as a palate cleanser while eating fatty foods. In essence, they were wondering whether there was something to the tradition of “red wine with red meat.” They discovered that when subjects took sips of mildly astringent beverages, including solutions containing grapeseed extract or the astringent component from green tea (a polyphenol called epigallocatechin gallate), in between bites of fatty dried meat, the tasters’ perceptions of both the fattiness and astringency were lower than when drinking or eating the samples with just rinses of water in between.

The authors theorized that this decrease in the perception of fattiness while sipping astringent solutions could be explained by the mechanisms through which our mouth actually perceives fatty and astringent foods. Both elicit tactile, rather than gustatory (i.e., taste), sensations. Astringent foods feel dry because the compounds that elicit this feeling actually bind to soluble proteins in our spit and cause the proteins to precipitate, or separate from, saliva. These proteins contribute to the lubricating qualities of spit, and without them the mouth gets that puckering, rough sensation. In contrast, fats interact with our mouth to provide a smooth feeling by actually lubricating the tongue, like grease on a chain. The authors concluded that astringent solutions are good palate cleansers for fatty foods because “astringency and fattiness can oppose each other perceptually.”

Based on this research, it seems the best palate cleanser for a given food may be one that interacts with our palate in an opposing manner . . . right?

TESTING IT OUT

In our first test, we presented samples of three different foods to volunteer tasters from the test kitchen: olive oil, hot sauce, and black tea, which represented fatty, spicy, and astringent foods respectively. Over the course of three days, we tested three palate cleansers in combination with those foods: a brief rest (thank you, Scott Carney!), unsalted saltines and water (thank you, sensory scientists!), and no palate cleanser at all (with neither rest nor saltines and water). Our volunteers tasted the food, rated its attribute on a nine-point scale (mouth-coating for olive oil; spiciness for hot sauce; astringency for black tea), used the palate cleanser, and repeated for a total of three tastes per food. We compared the ratings that tasters provided for the first and third tastes, to see if the palate cleansers affected the ratings over the samples (with the ideal palate cleanser resulting in the same score over all three samples). The only test in which there was any significant difference was for the olive oil tasted without any palate cleanser at all. Tasters reported that the degree of mouth-coating increased from the first to the third sample.

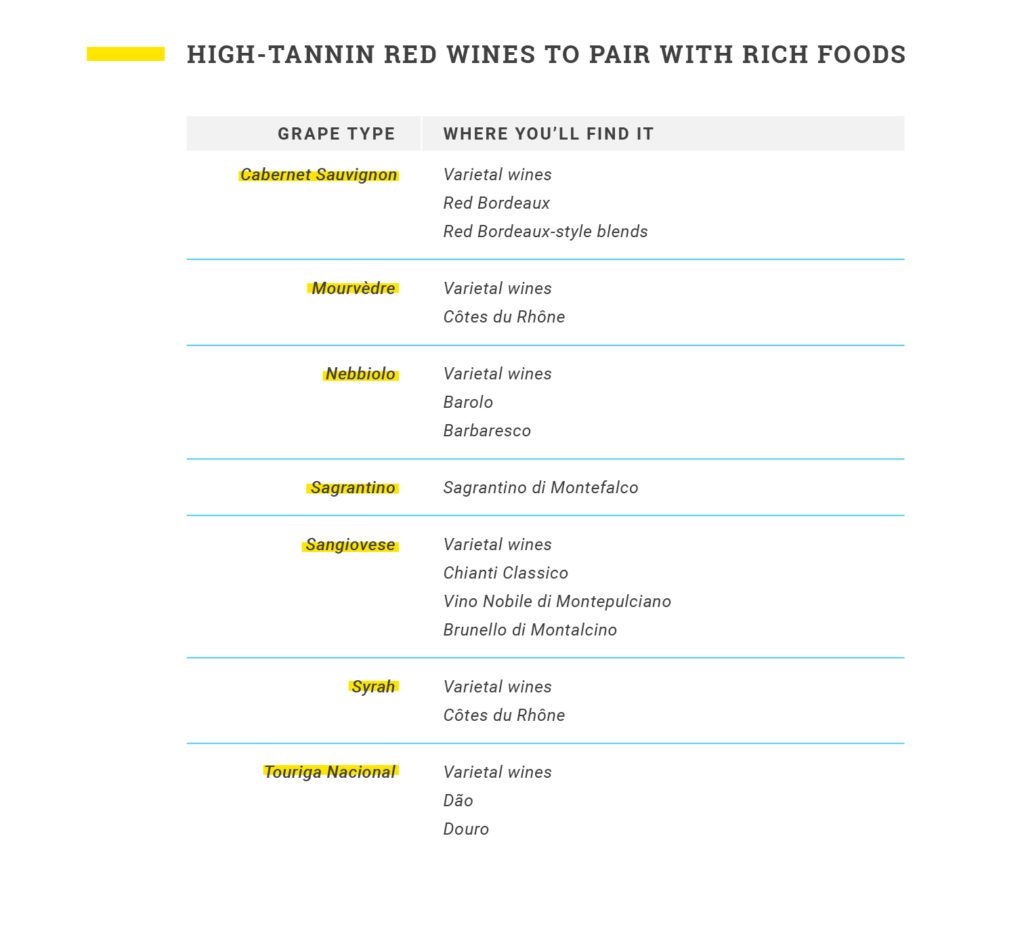

We wanted to dig deeper into the effects of fatty and highly astringent foods on our perceptions. To do this, we conducted a second test that we started with a trip to the wine shop. We wanted to find out if pairing astringent beverages, such as certain varietals of red wine, and rich foods could actually cancel each other out in the mouth, as suggested by the results of Breslin and co-workers study described above. Tannins, polyphenols found in red wine, cause an astringent sensation in the mouth through the precipitation of saliva proteins. We chose two red wines with different levels of astringency—the first an easy-drinking red Beaujolais, the other a very tannin-rich Sagrantino—and had a group of lucky America’s Test Kitchen employees measure the wines’ effects on the mouth-coating quality of olive oil.

The results? After five consecutive tests, alternating sips of olive oil and wine, testers reported that the astringent, tannin-rich wine cut the feeling of fat in their mouth more than the less astringent wine. One taster remarked, “It almost felt like the oil and wine were cancelling each other out on alternate sips.” While another taster said that the very dry and astringent Sagrantino seemed “to temper the fattiness of the oil.”

What does that mean? Serve your rich and juicy rib-eye steak with a more tannin-heavy red wine.

Photography by Kevin White