Nothing may ever unseat IPA as the ruling style of American craft beer, but many have tried: saisons, hoppy lagers, and session beers included. Today, the darling of the American craft beer scene is sour beer, which, if you haven’t had it, is just what it sounds like. Sours are tangy, with the acidic bite of lemon, vinegar, tart strawberry, or even a candy like Warheads. The growth of sour beer brewing reveals a new interest among American craft brewers in experimenting with yeast, microorganisms, and the fermentation process itself.

The result of the addition of acid-producing microbes during the beer-making process, sour beer has existed as long as beer itself. Before modern sanitation developments and the advent of pasteurization, naturally occurring bacteria could easily infect and sour a barrel of fermenting beer. As Michael Tonsmeire writes in his seminal book American Sour Beers, Europeans embraced that souring process and made it intentional with the emergence of tart styles like lambic and gueuze in Belgium and Berliner Weisse and gose in Germany. But for a long time, brewers didn’t understand much at all about the science behind these sour beers. The process, then and now, was to infect beer with wild yeast and microorganisms—either by allowing it to come in contact with microbes naturally or by directly adding bacteria culture into the beer—and sit back while it ferments into something complex, weird, and, in many cases, uncontrollable. Even brewers who have found ways to tame that process find it difficult to pull off every time. That’s why blending several batches of beer has become a vital part of the process for sour beer brewers who are looking to achieve a consistent taste among batches. Nevertheless, things still sometimes go irreparably and inexplicably wrong. “One of the biggest challenges is, you have to accept you’re going to dump some beer,” says Vinnie Cilurzo of California’s Russian River Brewing Company. “That’s just part of the [sour beer] game.”

There certainly wasn’t much information available in the United States in the late 1990s, when American brewers started experimenting with sour beer. There were no how-to books or Internet forums available. Cilurzo only knew of two other American brewers interested in sours with whom he could talk shop: Peter Bouckaert at New Belgium Brewing Company in Fort Collins, Colorado, and Tomme Arthur, then head brewer at Pizza Port in Solana Beach, California. He befriended Belgian brewers renowned for their lambic styles, too, but even they couldn’t tell him how much yeast and bacteria to add to his beer. “It was literally just having to just teach myself and learn by trial and error,” he says.

With Russian River, New Belgium, and Pizza Port paving the way, American craft brewers have reinvented sour beer over the last 20 years. “Craft brewers have now taken old-world beer styles, given them new-world twists, and flexed their muscle,” says Julia Herz, craft beer program director of the Brewers Association. “You have this explosion of acidic-forward beers.” Now, as sour beer rises in profile, brewers and scientists alike continue to experiment and demystify the science behind this unique style of beer. Along they way, they’ve discovered new techniques that lower the barrier to entry of sour beer making and reduce the significant risks that can accompany the brewing process. As a result, American sour beers are becoming increasingly accessible. But will they ever become truly predictable?

MANY ROADS LEAD TO SOUR BEER

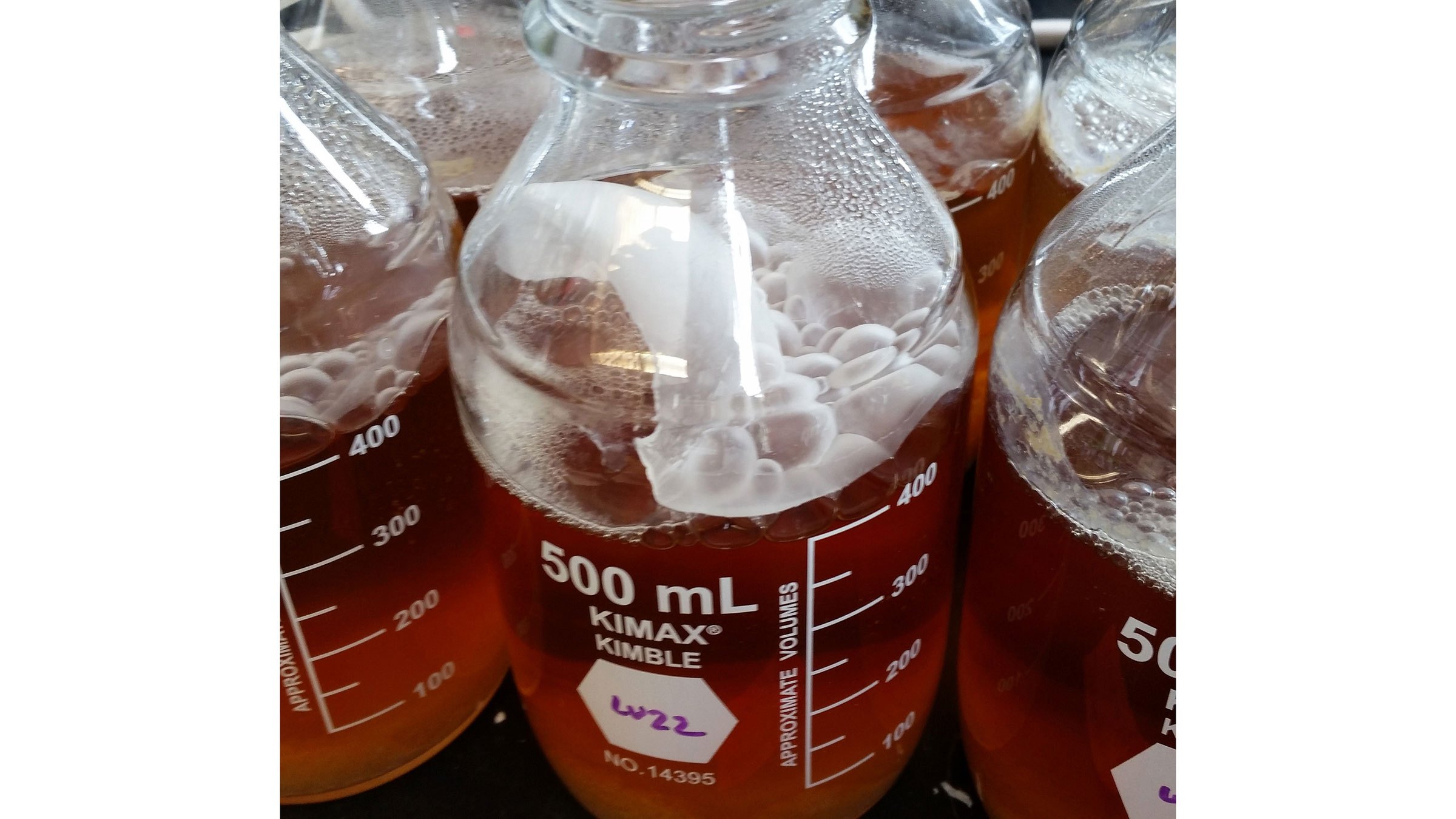

“This whole barrel-aging and spontaneous fermentation—it’s pretty magical when you get it right,” Cilurzo says. Brewers often describe the process of making sour beer that way. Sour beers typically begin the same way as any other beer: Brewers take grain and break down its starches into sugar, resulting in a liquid called wort. They boil and add hops to the wort, and finally add yeast to ferment the wort’s sugar into alcohol, creating beer.

And there is more than one way to acidify beer. Brewers use a variety of techniques to achieve sourness. At the more “magical” end of the spectrum is the traditional method of Belgian lambic making, in which wild yeast and bacteria infect a beer barrel left open to the air to naturally create acidity during the fermentation.

Other brewers start with “clean” beer—lagers, ales, IPAs, and the like—and allow it to undergo a second fermentation process with a cocktail of microorganisms that transform sugar into lactic or acetic acid, which you can find in yogurt or vinegar, respectively. Like Cilurzo, many brewers include Brettanomyces, a yeast that often occurs in spontaneous fermentation and inhabits the likes of fruit skins, in this mix. It doesn’t actually create acidity, but Brettanomyces complements the souring process by further breaking down sugars and adding a funky, earthy, barnyard flavor that has proven an excellent partner to sourness.

Meanwhile, brewers like Cilurzo and Ron Jeffries of Jolly Pumpkin Artisan Ales add further complexity to their beer by aging it in wood barrels, which are naturally filled with their own wild organisms. Jeffries started out experimenting with souring beer in steel kettles with yeast and Lactobacillus bacteria (the same bacteria responsible for many of our lacto-fermented foods, such as yogurt, pickles, and kimchi), with mixed results. There wasn’t any information about how much yeast and bacteria to include in a recipe and there weren’t many strains of yeast commercially available. Those early beers “just never delivered the complexity” Jeffries was looking for in a sour beer. Instead, he developed a process in which he exposes wort to the air and then wood-ages the resulting beer in used oak barrels to introduce more microbes during a secondary fermentation. “It works and gives us a complexity you can’t get from the store-bought bacteria and yeast,” Jeffries says.

SOUR CHALLENGES

If infecting beer with bacteria sounds a little daunting, that’s partly why sour beer has been so niche. Making sour beer is risky business. If you’re brewing both regular and sour beer, you don’t want your sour beer bacteria to travel and infect all your other batches.

Russian River has led the way in mitigating cross-contamination, according to Herz. The California brewery is best known for its non-sour Pliny the Younger, an IPA whose yearly limited release draws masses of beer obsessives to the brewery and select bars around the country. Pliny is too precious to risk contamination with souring microbes, so from day one, Cilurzo has used entirely separate equipment for their clean and sour beers. “Knock on stainless steel, we’ve never had a cross-contamination,” Cilurzo says.

But what if a brewery can’t afford two sets of equipment? In recent years, those breweries have turned to a technique called kettle souring. Brewers inoculate batches of wort with bacteria, let it sit in the brew kettle for a couple of days, and then boil it to kill off the bacteria, all before adding the yeast. So it’s already sour by the time the yeast begins the primary, main fermentation.

“Kettle souring is certainly allowing more breweries to get into this,” Cilurzo says, “and it’s also allowing more customers to drink sour beers because it’s more accessible now. The flipside is you don’t get the depth of flavor [of traditional sour beers]” since kettle souring uses only Lactobacillus bacteria, not a mixture of microorganisms.

SCIENCE TO THE RESCUE

One Indiana University biochemist believes he has developed a new technique that addresses that problem: primary souring. In a recently released and not-yet-peer-reviewed study, professor of molecular and cellular biochemistry Matthew Bochman describes primary souring as “a novel bacteria-free method for sour beer production.” Instead of relying on bacteria to create the acid that makes beer sour, Bochman’s method uses five newfound strains of yeast that can produce lactic acid during primary fermentation.

Creating a complex-flavored beer depends on the mixture of organisms you put into it. Recent years have seen a trend in beer science toward bioprospecting, or searching for new sources of wild and local organisms. The more yeasts and organisms that are discovered to be able to contribute something to beer making, the greater the possibility for building even more complex beers or even approximating traditional spontaneously fermented styles. And laboratory techniques to test these components allow brewers to screen out the ones that yield bad results. Stephen Fong, a professor of chemical and life science engineering at Virginia Commonwealth University, and his lab work with local breweries to examine the organisms present in a successful batch of sour beer. They then sequence the DNA of the bacteria culture in order for the brewery to replicate it for future successful batches.

So far, Bochman says his newly identified strains of lactic acid–producing wild yeast are yielding beer with more complex flavors than a typical kettle-soured beer. Rather than a crisp, tart finish, these beers might also have fruity, earthy, or spicy notes. And it does so without introducing any bacteria at all into the brewery. “I think this could be a real game changer for craft beer because it will allow everyone to get into the sour scene, not just those that can afford separate equipment and facilities,” Bochman says.

But Tonsmeire doubts that the technique will bring a paradigm shift. While the early results of the study are promising, he believes brewers may still shy away from bringing any lactic acid producer into their ecosystem, for fear of cross-contamination. Even though yeast is larger and therefore easier to trace and kill than the tiny bacteria that could creep into small cracks and bedevil a brewery—which Bochman argues makes it safe to use—Tonsmeire thinks many brewers will avoid them just in case. “It’s science, but it’s also emotional,” he says.

Some brewers are already experimenting with these new yeasts, though. Upland Brewing Company, which has worked with fellow Bloomington, Indiana, local Bochman on its sour ale program, has conducted trials using four of the five yeast strains. Pete Batule, vice president of brewery operations, says the brewery particularly liked one of those strains, as it created fruity notes and a sharper finish with just the right amount of alcohol. It’s not as acidic as Upland’s other sours, but more so than their wheat beers. “It’s just another tool to innovate with and play with and make some more interesting beers,” he says.

THE PERFECT MIX

Science is proving useful beyond providing novel ways to control sour beer fermentation: It’s also aiding in analyzing the final product. “The final arbiter has to be: Does it taste good?” Tonsmeire says. Lauren Salazar, blender at New Belgium Brewing Company, agrees. “If you’re only looking at numbers and not thinking about how a beer tastes, you’ve already lost,” she says.

New data collection tools and techniques are helping brewers analyze the final products of their sour beer batches. As New Belgium’s wood cellar blender, Salazar tastes the beers in all of the brewery’s foeders (large barrels used for fermentation) and determines which ones to blend together to create a beer with the exactly right notes of fruit, florals, spice, and other flavors. Her sensory-focused responsibilities might be more of an art or a judgment call than a science, but even she is turning to objective analytics to help improve her processes. Once Salazar senses that a beer is ready, New Belgium has begun testing the beer to determine data markers such as the level of esters and alcohol, and the ratio of organic acids. “These are all the questions I’ve been dying to ask, but have been scared to wonder,” she says. “What makes a barrel done?”

Having data to explain the answer isn’t about to replace human tasters, but it will be useful for training new ones. Salazar is working now to train another employee how to gauge beer readiness and, by using both sensory cues and this new analytical data, she says, “We can [each] take a sample of [beers from] like 20 foeders and come up with the exact same answers.”

Even when there aren’t any answers or easy fixes, Cilurzo argues that more research always brings more power to brewers. It’s what has driven the craft beer movement in the first place. “The beauty of craft beer is the innovation side of it, whether it comes from a brewer or academia,” he says. “Where America used to be the laughingstock, we’re kind of leading the world now in brewing innovation.”

A STARTER GUIDE TO SOUR BEERS

Whether you’re looking for a gentle, introductory sour beer, with a hint of acidity, or a bolder brew with some barnyard funk, there’s a sour beer for you. With the help of American Sour Beers author Michael Tonsmeire, who’s opening his own mixed fermentation–focused brewery Sapwood Cellars, we compiled a list of nationally available sour beers you might sip this summer, along with some notes on their flavors and how they get their acidity.

Sierra Nevada Otra Vez

If you’re thinking about trying sour beer for the first time, consider starting out with Sierra Nevada’s Otra Vez. Tonsmeire says this beer is tart, but not shockingly so—its German gose style is high in lactic acid so its sourness is like that of yogurt, as opposed to the more vinegary taste of beers with acetic acid. Subtle flavors of prickly-pear cactus and grapefruit make it a great summer beer to boot.

Anderson Valley the Kimmie, the Yink, & the Holy Gose

If you want to understand what kettle souring is all about, keep an eye out for Anderson Valley’s line of gose-style beers. The Kimmie, the Yink, & the Holy Gose is soured in the kettle with Lactobacillus, with a tart but not too acidic taste that Tonsmeire says also makes it a good starter option. If you prefer fruity flavors, Anderson Valley also makes a solid Blood Orange Gose.

Lindemans Gueuze Cuvée René

It can be a challenge to find an American spontaneously fermented beer. Tonsmeire notes that this style is a big investment and the breweries who are experimenting with it haven’t scaled up distribution yet. Fortunately, Belgian brewers have been perfecting spontaneous fermentation for centuries. This gueuze—a blend of lambics—has the barnyard funk and complex acidity that comes from exposure to wild yeast and bacteria.

Jolly Pumpkin La Roja

Jolly Pumpkin Artisan Ales is also known for its complex sours since its wood-aged mixed-fermentation process does expose beer to naturally occurring microbes. La Roja is a great example of a Flanders-style sour, which originated in Belgium. Aged with cherries, this amber ale has a fruity sourness, some funk, and notes of earthy caramel.

The Bruery Tart of Darkness

Want to try a sour stout? The Bruery makes a fine rendition under its Bruery Terreux brand. Tart of Darkness is a traditional stout aged in oak barrels then soured with a house blend of bacteria and yeasts. Tonsmeire describes it as an approachable sour, not too funky or acidic. Roast from the malt melds together with light acid, fruitiness, and a little bit of added character from Brettanomyces.

Cascade Noyaux

For a taste of something really different, Tonsmeire recommends Noyaux from Cascade Brewing in Portland, Oregon. These brewers are known for their predilection for experimentation and Noyaux is a prime example: Its blend of blonde ales was aged in wine barrels with raspberries and the toasted kernels of apricot pits. Its acidity comes from that fruit as well as Lactobacillus. Aged in wood barrels, it has an oaky taste without the funk of Brettanomyces.

New Belgium Le Terroir/La Folie

On its own, New Belgium’s line of sours offers a great window into the world of this style of beer, thanks to its method of blending beers aged in enormous wood foeders populated with their own microflora. For an extremely puckering sour, Le Terroir is a wood-aged dry-hopped ale with fruity and tropical notes and a bit of earthiness. Tonsmeire also recommends La Folie, which he says is probably the closest an American brewery has gotten to a Flemish red, with its sweet, sour, and slightly vinegary taste.

Crooked Stave Hop Savant

Crooked Stave founder Chad Yakobson wrote his master’s thesis about Brettanomyces fermentations so Tonsmeire recommends looking to this Denver brewery if you want to give 100 percent Brett beer (beer fermented only with Brettanomyces yeast) a try. Hop Savant is a dry-hopped American pale ale. It has a strongly funky, earthy taste, plus a crisp sourness that’s a bit on the citrus side.

Russian River Sanctification

Russian River also makes an excellent 100 percent Brett beer, Sanctification. It’s not distributed very widely, but that could change as the brewery is currently building a separate sour beer facility.

Have a favorite sour beer we didn’t mention? Tell us about it in the comments, below!