On a freezing December morning, I visited the Open Agriculture Initiative at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, and talked with Director Caleb Harper. Harper and his team aim to reinvent the future of farming, both locally and globally. Their work features open-source Food Computers, which are enclosed containers for growing plants in controlled environments. Food Computers use robotic systems to control the conditions inside them, known as the “climate,” from temperature and humidity to dissolved nutrients and carbon dioxide. Here’s what we discussed:

Cook’s Science: Tell us about your work. What is the Open Agriculture Initiative?

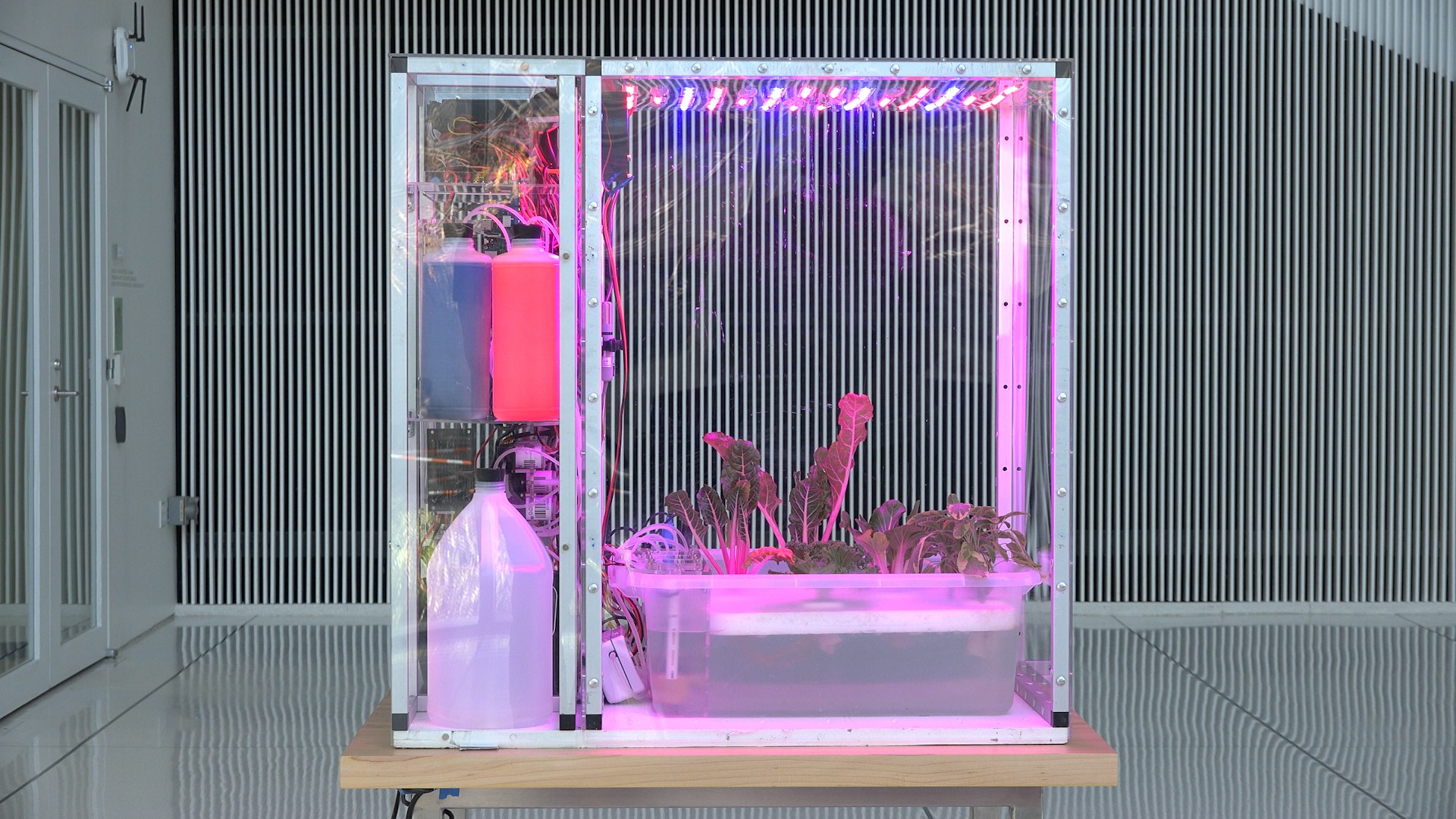

Caleb Harper: [Open Agriculture is] a big initiative, and there are a lot of problems in food. I think our work will address many of them, but the biggest problem I see us solving is creating a next generation of farmers. A lot of our focus is on developing tools…which we call Food Computers as a general category. We have the Personal Food Computer, which we open-sourced six months ago and now has been built in 20 countries on 6 continents. These Personal Food Computers don’t grow a whole lot of food. [They’re] not about that. They’re about growing intelligence, growing skills, growing knowledge, especially [when they are used in schools]. They help teach about chemistry and biology, but also about data science and sensor science and electronics and coding. It’s been really successful in a lot of schools.

The next size up from the Personal Food Computer is what we call a Food Server, which is the size of a shipping container. Our last tool is the Food Data Center, which is the scale of a warehouse. This gets into real [food] production. But the cool thing is what links all three of these tools —the data we collect. We collect climate data that will tell us how that climate [within the Food Computer] will cause that plant to express [its genome]. So, the natural climate in Mexico, or the climate in Napa, or Bordeaux, or any other Food Computer climates we want to experiment with, they are the generators of flavor, color, texture, and size. And so, as kids, adults, scientists are doing experiments with Food Computers, they’re generating climate data. The technology between the three types of Food Computers is a bit different, but the data they produce, which we call ‘Open Phenome [Library],’ is really a sort of crowd-sourced science project.

CS: What problems are you and your team working to solve?

CH: I think probably one of the biggest problems is that people don’t really know a lot about food. General, normal people haven’t had to be involved in food in a long time. My ancestors came over during the land rush and were farmers but they left at some point because farms started to aggregate, and you started to have very big farms in the United States. That’s resulted in 2% of our population being farmers and their average age being 58. Think about that. A whole, important group of people, and this is pretty consistent around the world, is almost in their 60s. So, who’s the next generation of farmers? I think it’s going to be kids who are interested in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and STEAM. They’re going to be scientists who apply out-of-field knowledge [to agriculture]. Agricultural research has gone very deep but very narrow for a long time. And now I think we’re going to expand it across a bunch of different fields.

CS: It sounds like providing open-source material for making the Food Computers, and open-sourcing the data they collect, is a key part of your work. Why is this so important to you?

CH: There [are a] lot of people doing what I’m doing, in a way. You’ll see shipping container farms, you’ll see warehouse farms, you’ll see tiny farms in apartments, and I think that’s awesome. But the biggest thing I thought was missing was that everyone’s designing their own little solution and then they’re putting a patent on it. I was watching this happen, I visited all of them. I realized that informational transparency was necessary for this to do any good for the world. I want everyone to be able to tinker around with [Food Computers] and come up with new solutions because it’s the beginning, it’s not such an evolved field. And then I realized that even somewhat more than the machines, the data is also really important. Once I figured that out, I just started putting climate recipes in the public domain because I don’t want to see a day when climate recipes are patented, because there’s so much to learn. We have all this new technology like [Artificial Intelligence] and machine learning and computer vision. What people don’t talk about is that it takes massive data sets to use that stuff. You need trillions of data points. In this category we’re working on there are literally no working data sets. So how are we going to get some of the smartest people in the world to help us with the future of food if there’s no open data for anybody? And that became a really big lightbulb—I said I have to build the world’s biggest data sets for the future of farming so they can be used by smarter people than me, by algorithm folks, by chefs, so it has to be open. There’s no way I think this will be successful if it follows the very traditional agriculture model of closed source intellectual property.

CS: You mentioned chefs. How do you see your work interacting with chefs and restaurants?

CH: If you can imagine using Food Computers to grow ancient seeds, rare seeds, heirloom seeds . . . we grew some tomatoes in the lab that hadn’t been grown in 150 years. I think this can give a chef access to be really creative with things that aren’t available at their local level.

The other thing is approaching food like wine making. Wine makers will [deprive] the vineyard of water at a certain time to increase sugar production in the grapes, they’ll do all kinds of microclimate adjustments to achieve that 100-point wine. I think we’re going to see the same thing for food. Like a tomato that has that amazing, robust, ‘Tuscany in the summertime on the north slope’ taste, but is grown in Detroit [in a Food Computer]. It’s a lot about flavor. It’s about getting [chefs] access to things they haven’t had before. And I think a lot of chefs right now want to know about farming.

CS: So what’s next for you and your team?

CH: So much cool stuff. We just released version 2.0 of the Food Computer at the White House a few weeks ago. We are in full mode of developing that and making it better and getting it out to schools. I think 2017 will see hundreds of Food Computers in schools across the world. We have a project with the World Food Program where we’re bringing some [Food Computers] to refugee camps. We have our new lab [in Middleton, Massachusetts]. We’re going to do some ancient and rare genetics in there. We will be launching our not-for-profit, which at its core, is like a trust for the data, for the software and the hardware.

CS: What would you share with our readers who might be interested in getting involved with food computers and the future of farming?

CH: I would say, if you’re interested, join the forum, think about building a food computer, or think about funding one for a school and giving it as a gift, especially if you’re a parent.

The more “nerd farmers” we have, the better. If you want to grow [plants] and you have a hard time growing, use [the open-source Food Computer and climate recipes]. And when you grow, your data will be useful to someone else and you’ll be able to get data back. Once you get into this little “nerd farmer” community, amazing things start to happen. There are lots of questions and it’s early days, but it’s a really fun time to get involved because there aren’t many people who are that much better than anyone else. So, we’re going to explore and we’re going to have fun. But eventually that data will be used to grow food in cities in the future. I think that’s the legacy of the project.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Photos courtesy of Open Agriculture Initiative, MIT Media Lab.