When you melt a nice young Monterey Jack cheese, it softens and oozes and stretches smoothly. In that simple act, there’s a lot going on. The fat and moisture that make up the bulk of the cheese are an emulsion, with particles of fat aswim in a watery medium. They are held together by proteins that act as emulsifiers. And the proteins cling to each other, with the help of calcium, forming a mesh throughout the cheese.

As the fat warms up, it turns from solid to liquid, which starts the oozing process. At the same time, heat makes the proteins loosen their gentle hold on each other, easing into a slouchy matrix that stretches along with the now-runny emulsion. The water in the cheese stays juicily mingled with the fat. Perfect.

Alas, not all cheese melts as graciously as Jack. A sharp, long-aged Gruyère, for instance, will tend to separate into a lumpy, chewy blob of protein sitting in a pool of liquid fat. Not perfect.

The reason? Over the months that the Gruyère was aging, much of its water evaporated. That concentrated the cheese’s wonderful flavor—one reason we love aged cheeses—and bumped up its relative fat content. An emulsion is a delicate thing, and with less water present to hold up its side of the arrangement, the fat is much more likely to break out of its emulsified state and puddle up when melted. Moreover, aging also causes the cheese’s proteins to clump in little compact groups. Those tightly clustered tangles of aged proteins are too wrapped up in each other to emulsify well, and because they’re so intertwined, they don’t come apart nearly as easily when heated. Instead, they stay put while the fat melts and drips out around them.

The creators of smooth processed cheeses like Velveeta or American cheese have a solution: a salt solution. Sodium citrate is the best known of a few different ingredients known as melting salts, which facilitate the melting of old or stubborn cheeses. It’s a white powder with a salty-sour taste, but in cheese, its taste isn’t noticeable. The tight-knit proteins that hinder smooth melting are bonded to each other with the help of calcium ions. When you warm up a mixture of cheese with the addition of liquid and a small amount of sodium citrate, the sodium substitutes itself for some of the calcium that’s helping the proteins cling. As the cheese is heated, the proteins separate from each other and again act as emulsifiers, strengthening the emulsion by holding fat and water together.

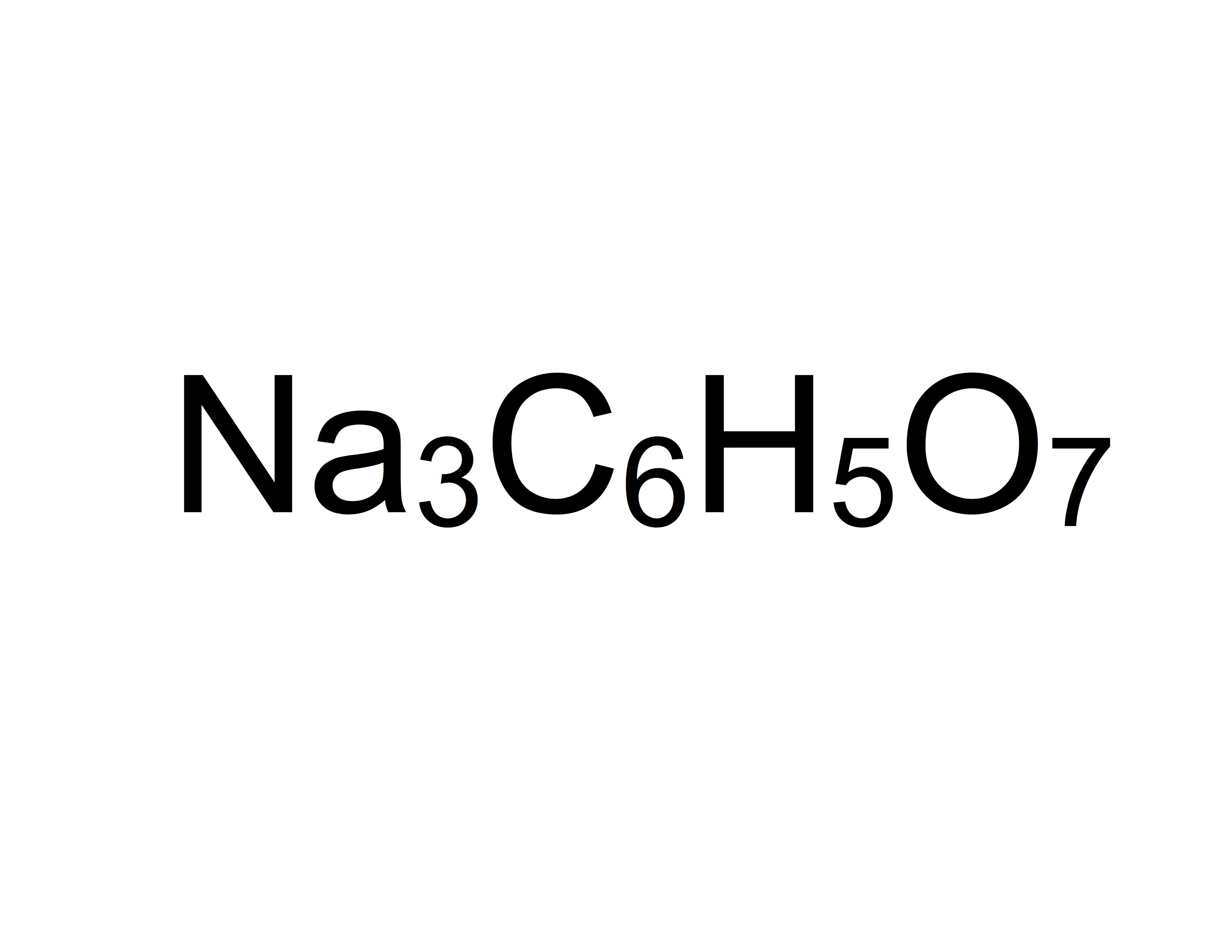

The result is a stable, smooth melt with no lumps and no leaks—perfect for fondues and cheese sauces. The chemical formula for sodium citrate even spells out “nacho”. Behold: