After a 150-year absence, milk punch is back. Newly popular with the mixology set, this drink is more a technique than a particular recipe, much as punch is a format rather than a formula. Today’s bartenders are not only experimenting with the range of ingredients that go into the cocktail, they are also experimenting with the technique itself. To understand more about the drink, how it’s changing, and how to create a great recipe for the home bartender, we hit the bar scene—and spoke with as many professional milk-punch makers as we could.

There are two kinds of milk punch. The first, typically called brandy milk punch or bourbon milk punch, is popular in New Orleans, is citrus-free, and includes milk. The second type, often called English milk punch or clarified milk punch, is what we’ll focus on here. From this point on, we’ll refer to it simply as milk punch.

The base recipe for milk punch includes citrus juice or another acidic ingredient. Milk (usually hot milk) is added to the mixed cocktail, curdling the milk, and then the punch is strained to remove the curds. The process removes most of the color and cloudiness from the drink, clarifying it, and it preserves the cocktail from spoilage for months or even years if kept cool. After Charles Dickens died in 1870, bottles of milk punch were found in his wine cellar.

The concept of clarifying cocktails with milk might seem a bit odd today, but in the milk punch heyday—the 1700s through the mid-1800s—spirits would have been far rougher around the edges than those we enjoy today, and in addition to clarifying and preserving the drink, the process also softened the harsh flavor of the booze. The resulting drink is unctuous and silky, clear and only subtly milky, with softer, mellow flavors.

And today? You may not need to soften the flavored edges of your spirits, but the drink offers advantages to bartenders in top cocktail lounges: It can be batched in advance for speed and consistency rather than assembled to order, it does not spoil if handled appropriately, and it makes serving easy. Most bartenders simply pour refrigerated milk punch into a stemmed cocktail glass or over a large ice cube. At most, it’s mixed with soda water and garnished with a citrus peel.

This means that milk punch also a great option for the home bartender. It can be mixed and clarified ahead of time, then stored in the fridge, ready for your next holiday party (or after-work tipple). The milk punch process can be applied not only to traditional punch recipes, but to other classic drinks, giving a White Russian, Midori sour, or Ramos gin fizz an inventive edge.

BACK TO BASICS

The earliest known milk punch recipe, as reported by cocktail historian David Wondrich in his book Punch, dates to 1711, and is attributed to housewife Mary Rockett. That recipe calls for a gallon of brandy, five quarts of water, eight lemons, and two pounds of sugar. To it, two gallons of scalding hot “new milk” are added, and after an hour, it is strained through a flannel bag.

Benjamin Franklin wrote a recipe for milk punch in a letter dated 1763. It’s a bit boozier and less sweet than the earlier recipe, but sticks to the same basic formula, with added nutmeg.

By the time the first bartenders’ guide was published in 1862, Jerry Thomas’s recipe for English milk punch contained brandy plus rum and arrack, lemons and pineapples, green tea, cloves, coriander, and cinnamon. Many of today’s bartenders use this recipe as their starting point before playing with everything from camel to coconut milk and rejiggering the process.

WHAT IS GOING ON HERE?

To understand what’s happening when making this clarified concoction, we can look to consommé, wine making, and sauce making for help.

To make consommé, egg white proteins coagulate in a cloudy stock as it’s heated, forming a 3-D network of sorts, trapping the liquid’s cloudiness-producing particles and forming the solid “raft,” which eventually floats to the top. The raft is skimmed off and the remainder is a clear liquid.

For milk punch, bartenders accomplish much the same thing but use milk proteins instead of egg white proteins; use acids to curdle the milk and coagulate its casein proteins rather than heat alone; and the raft of curds (often called a nest) sinks to the bottom of the container instead of floating to the top. In the cocktail world the technique is generally called milk washing and can be used on spirits alone or on a full cocktail. Egg washing is the same process but with raw egg whites instead.

In addition to clarifying, milk washing also softens the harshness of the flavor of the punch ingredients, stripping out astringent-tasting tannins and other polyphenols. Tannins are most noticeable in foods and drinks like wood-aged spirits, red wine, black tea, the skins of nuts, and immature fruit. (Tannins and woodiness are desired flavors in many of these other drinks, but too much of a good thing is problematic – think over-steeped tea. Removing them in milk punch can fix some excessive-tannin flaws, if present, but also helps marry flavors together into a soft and luscious whole.)

When consumed alone, the tannins in these foods and beverages bond with proteins in our saliva, giving us that astringent sensation in our mouths. But if we add milk to the tannic liquid, the tannins will bind with the milk proteins instead of those in our saliva. In sauces with red wine reductions, for example, tannins concentrate as the wine is boiled down. This means that they have the potential to taste overwhelming, except for the fact that proteins from the sauce’s meat bind with wine tannins to help neutralize the astringent sensation.

Milk, along with other animal proteins like egg whites and even blood, have long been used in the wine fining process to reduce tannins and help settle out solids from the fermented juice. But this process generally uses small amounts of fining agents, like Bentonite clay and Chitosan, in a large volume of wine and can take a long time to settle. Milk or egg-washing, on the other hand, is done relatively quickly to preserve fresh or spoilable ingredients.

PROCEDURAL MATTERS: CURDLE IT

Traditional recipes for milk punch call for the cocktail ingredients to be combined and added to near-boiling milk, before allowing the cocktail to rest, and then straining it. But a look at current bartender practices opened up a whole new realm of choice for the cocktail maker—from milk temperature, to the order of alcohol addition, to resting time, to choice of filter. And that’s not even including what ingredients you decide to put in the damn thing.

First up? The temperature of the milk. Some bartenders have abandoned its near-boiling status. Nico De Soto, the beverage director at Mace in New York and Danico in Paris, and Chad Arnholt, one half of the consulting firm Tin Roof Drink Community along with Claire Sprouse, say it’s not really necessary to heat the milk, while others claim it is crucial. But nearly everyone agrees that you add the cocktail to the milk, rather than adding the milk to the cocktail, so that it does not instantly curdle.

Some bartenders also wait to add the alcohol until after the milk is curdled. Eamon Rockey of New York’s Betony curdles the warm milk with only the citrus first, then adds the remaining nonalcoholic cocktail ingredients and filters (the booze comes later). Luuk Gerritsen of the forthcoming Luke’s Cocktailbar on Curaçao says, “I feel that clarifying without alcohol gives cleaner results, though with brown spirits you don’t really have a choice [if you want your punch to be clear].” In contrast, De Soto says he finds the final drink to be more “harsh” if you wait to add the liquor until after clarification. Milk washing also strips out woody flavors from aged spirits, so much of this before-or-after decision is based on whether you want those flavors integrated into the cocktail or kept out.

PROCEDURAL MATTERS: REST IT

As the milk breaks, most bartenders continue to stir gently, and then wait for anywhere from ten minutes to an hour to let the mixture fully curdle and settle. (And some wait a few days.) Bartenders have also taken to letting the ingredients rest at different stages, to better integrate flavors and to make a richer cocktail. After adding milk to curdle the mix, bartenders, including Restaurant 1833’s Josh Perry in Monterey, California, and Donnie Pratt of Cucina 24 in Asheville, North Carolina, let theirs rest overnight before straining.

Gareth Howells of VYNL in Manhattan rests his punches at three different points: during the initial mixing of the cocktail (“I find it offers the finished product the best depth of flavor,” he says), after curdling but before filtering (“I find it really mellows out and softens the finished product”), and after the product is filtered but before serving (“this resting period really helps harmonize the flavors of the punch as ‘just filtered’ punch can tend to drink very bright and sometimes a little raw”).

PROCEDURAL MATTERS: FILTER IT

The ingredients are mixed, the milk is curdled, and you’ve let the cocktail rest (at least a little while). Now it’s time for the tricky part: straining the mixture through a filter. The curds did the work of clarifying the cocktail, and now they need to go.

It’s important to remember that the curds filter the cocktail, not the cloth through which the liquids drip out. As you filter through a cloth, the remaining stray proteins and cloudy bits left in the liquid will get stuck in the nest of curds that has formed at the bottom of the container. Milk punch makers are careful not to disturb the nest too much, because should a channel open up in it for liquid to flow through the nest without passing through the glop, the cloudy suspended particles will be carried along the liquid.

As for the choice of filter? Many bartenders polled use a Superbag (an expensive net bag with fine holes), or cheesecloth lining a conical chinois or china cap. Arnholt has settled on a cooking oil filter (which looks like a big coffee filter) inside a china cap. Rockey says, “The most effective filtration support mediums are those that are a single layer, durable, tightly knit, organic material; a standard restaurant tablecloth is a great example of this type of filtration support medium.”

INGREDIENT MATTERS: MILK

While milk punch was traditionally made with whole milk, today the milk choices (everything from fat level to which animal or nut it’s derived from) are endless, and bartenders have been experimenting.

Gerritsen experimented with several types of milks for his punches. He found that nonfat and low-fat milks didn’t curdle well, that whole and half-and-half were best (and that unpasteurized milk was even better). He was able to use cream, but disliked the flavor, saying it gave an “off-putting fatty nose” to the final punch. Sour cream failed, but buttermilk lent a “non-citrus acidity” to the final product. Arnholt called the buttermilk clarification “cheesy” in a way that doesn’t sound pleasant, and also prefers fresh, lightly pasteurized milk to “macromilk.” Christopher Sinclair from the Red Rabbit Kitchen and Bar in Sacramento uses half-and-half, partly due to its high fat content, but also because that’s what they typically have behind the bar. Peña uses 2 parts whole milk to 1 part half-and-half.

The milk doesn’t have to come from a cow. Gabriella Mlynarczyk, beverage director at Birch restaurant in Los Angeles, experimented with full-fat cow milk, full-fat goat milk, full-fat sheep milk, and full-fat coconut milk. “Goat gave me by far the best flavor and most rapid clarification,” she says. At Loló in San Francisco, bartenders use a ratio of 1 part goat’s milk to 5 parts cocktail in their milk punch. And Paul Bradley of Gold on 27 in Dubai says he once made a date and camel-milk punch as an experiment.

Nut milks are another story. Rockey says, “While some vegetable milks (like soy milk) contain a great deal of protein and can be curdled, I have never had success with vegetable milks at producing clear milk punch.” Kaiko Tulloch of Lucky Liquor in Edinburgh says she tried almond milk but ended up needing to add whole milk for her “clarified horchata” with tequila. Perry mixes coconut milk with cow’s milk in his recipe for the same reason.

INGREDIENT MATTERS: ACID

But milk is only one half of the magic; acid to curdle it is the other. The bartenders we spoke to have used lemon, lime, grapefruit, orange, pineapple, and yuzu juices, white verjus, and kiwis (in oleo saccharum form) as the acid agent in their punches. Some have even gone so far as to use powdered citric acid, malic acid, or lactart.

Bartenders say that not much milk nor much acid are strictly necessary to make the milk curdle, but that increased amounts are a matter of final recipe taste and ease of filtering. Rockey notes, “Very little milk is actually required to clarify a punch; it is more important to consider how much surface area the broken curds will need to cover to create a sufficient nest for the punch to clarify.”

In other words, you want enough of a bottom layer of curds for the liquid to run through during filtration, or else you’ll get colored solids in the final result. Additionally, more milk should lend a more creamy and rich finished punch, and typically a good amount of acid is generally required for a balanced cocktail anyway.

BACK TO THE TEST KITCHEN

[Ed note: After Camper English delivered his milk punch story to the Cook’s Science team, Executive Editor Dan Souza began developing his own recipes for the home cook. The following is from his perspective.]

I could happily keep testing milk punch recipes forever. I don’t often say that about a recipe I’ve been toiling over for weeks, but milk punch is just different. Camper’s exhaustive survey of professional bartenders’ riffs on the milk punch form should give a pretty good hint at how many variables there are to play with. But beyond providing an excuse to geek out on casein proteins, pH, and filtration, milk punch is just fun and tasty. The transformation from cloudy, inky punch to the crystal-clear blush of a pink wine is very satisfying. And that’s all before you even get drunk on the stuff.

I started by using a very basic punch recipe, with brandy, lemon juice, and sugar. I figured I would iron out all the procedural details, so I could move on to flavor variations.

My first big question: Is it actually important that you add the punch to the milk and not the milk to the punch? I wrote in my notes that this rule smacked of old-timey milk punch lore that was probably ripe for debunking.

I was wrong.

Just a couple of tests proved that order of operations is very important. Adding milk to the punch invariably resulted in a twisted mass of curds suspended irregularly within the punch. This happens because the milk comes in contact with the highly acidic punch and coagulates on impact. The result is that only a portion of the punch actually gets clarified, giving you a colorful (in a bad way!), cloudy drink. Adding the punch to milk might not seem all that different at first glance, but it’s all about rate of acidification. As the (acidic) punch streams into the milk, it slowly (relative to the milk-into-punch method) drops the pH of the milk. Once all the punch is in the milk, the pH is low enough (lower than 4.6, the pH at which casein proteins precipitate, or fall out of solution) for it to curdle. At that point the milk and punch are evenly mixed, so when the milk curdles it’s able to trap impurities from the entire mass.

I was also incredibly curious about the hot milk–cold milk rift in milk punch practice, so that’s where I focused next. With three different base punches I tested 40-degree-F whole milk versus 180-degree-F whole milk (adding the punch to the milk in each case, of course). The biggest difference I noticed was the size of the curds that formed. When I used hot milk, the curdling reaction happened more quickly, and I ended up with larger curds. When I used cold milk, the curds were far smaller and more evenly distributed throughout. Just as with order of operations, the larger, faster-forming curds often didn’t clarify the drink quite as thoroughly as the smaller, slower-forming curds. I say “often” because there were plenty of times that hot milk worked just fine. But I consistently got the best results using cold milk. Added bonus? No need to heat up the milk.

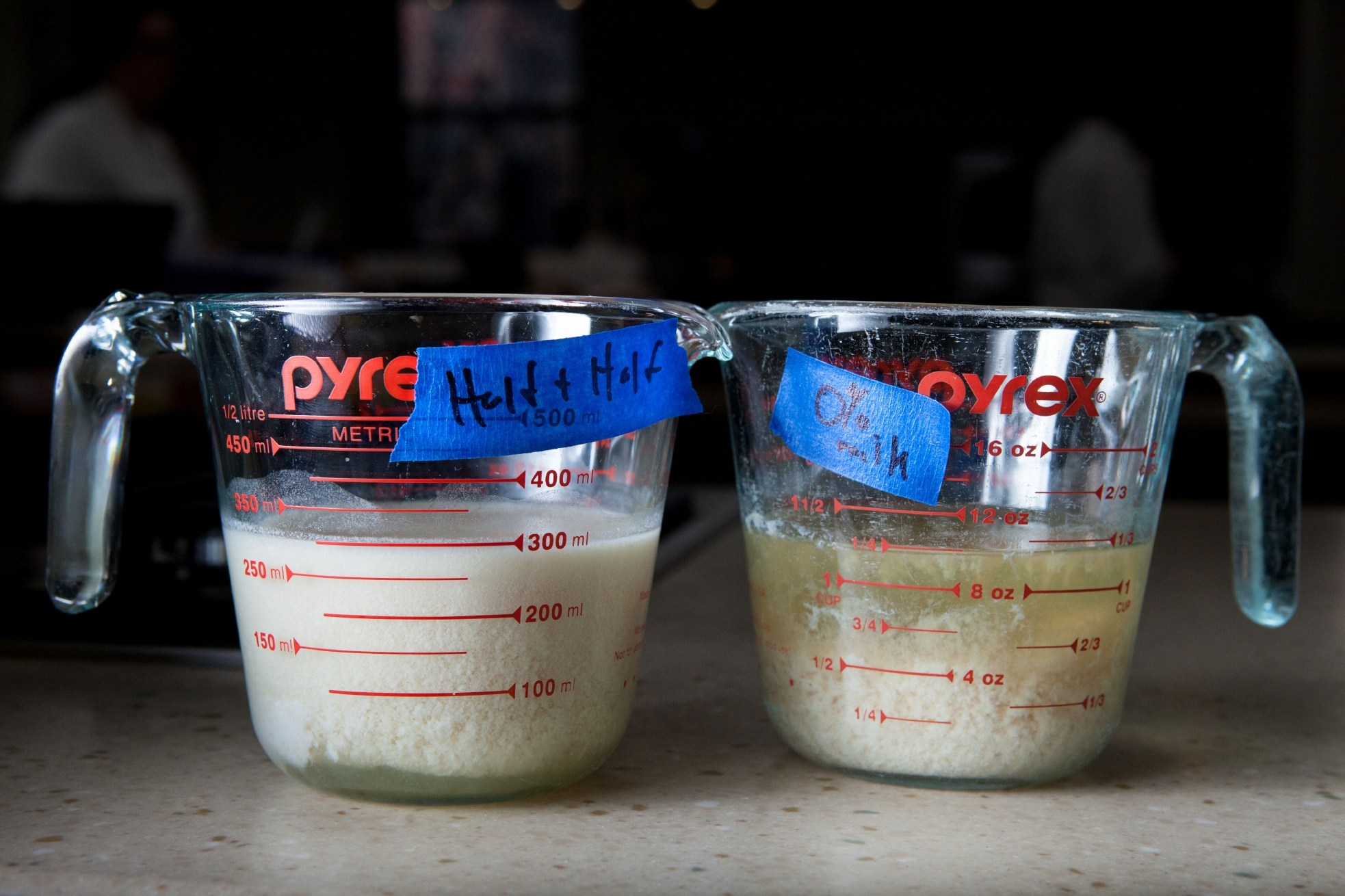

So at this point I knew I would be adding punch to cold milk. Great! The next logical question is what type of milk is best? I limited my testing here to pasteurized, homogenized dairy from cows and focused primarily on fat content. I had a hunch that using a lower-fat milk, which is proportionally higher in protein (the stuff that does the clarifying) would make for a better clarification.

I was wrong. Again.

My tests with skim milk looked promising at first—the milk mass curdled nicely and fell to the bottom of the glass much faster than with whole milk—but the resulting milk punch was always cloudy. Half-and-half reacted completely differently. Thanks to its abundant fat content, the curds never actually sank to the bottom, but rather stayed suspended at the top. Half-and-half often produced a relatively clear punch but not every time. Call it the goldilocks effect, but middle-of-the-road whole milk emerged as the best clarifier in my tests.

Finally I took a look at filtration. As with every recipe I test, I wanted to start simple and only introduce special equipment or techniques as needed. Luckily for me (and, well, everyone who likes convenience and drinking), a coffee filter set in a fine-mesh strainer does the job admirably. The real key to getting superclear milk punch is pouring the curdled punch into the strainer slowly, and after it drains completely, filtering it through once again. The coffee filter does a lot of the heavy lifting, but the nest of curds sitting on the bottom of the filter sops up the really fine stuff.

At this point in the process, I was ready to play around with actual recipes. And so I started at the beginning—the very beginning. I made a batch of the earliest known milk punch recipe, which is credited to Mary Rockett in David Wondrich’s lovely book Punch. It’s a simple mixture of brandy, water, lemon juice, lemon peel, and sugar that, once clarified, looks like chardonnay and drinks like a refreshing limoncello cocktail. It calls for a 4:1 ratio of punch to milk for the clarification, which turned out to be a great ratio for all my recipes. My adaptations to Rockett’s original recipe are few: I use cold milk in place of hot, add orange peel and orange juice to the lemon for a more complex citrus flavor, and scale it down to make one quart. You can get my recipe here.

While I was reading Wondrich’s book, I was pulled in by a couple of other old punch recipes that he had uncovered—but ones that weren’t traditionally clarified with milk. One was Ruby Punch, a recipe Wondrich found in Jerry Thomas’s Bar-Tenders Guide from 1862 that features a seriously tasty combination of black tea, ruby port, lemon, and a funky rum-esque liquor called Batavia Arrack. The other was Billy Dawson’s Punch, which in classic English punch form, combines both brandy and rum with, oddly enough, some dark beer like porter or stout and richly flavored Demerara sugar. They are both delicious on their own, but I really loved how they changed with milk clarification.

The Ruby Punch, originally rich in tannins and color from both strong tea and port, turns silky smooth and fruity after clarification, and its color change is dramatic—from inky plum to a light rosé wine. Come to think of it, if you like rosé, I think you’ll love this one. Billy Dawson’s concoction is a more spirit-forward, less fruity affair that would feel right at home in a snifter sitting on a mahogany desk surrounded by leather-bound books (I think you know what I’m talking about). My milk-clarified version is full-bodied, amber-hued, and smooth. You still taste the brandy and the molasses-like demerara, but there are no rough edges to keep it from going down easy.

RECIPES

Mary Rockett’s Citrus Milk Punch

Photography by Kevin White.