The flavor of most cocktails entails a careful balancing act between liquor, sugar, and a sour element, most commonly lemon or lime. The margarita, cosmopolitan, mojito, mai tai, daiquiri, gimlet, sidecar, collins, and every drink with sour in the name are just a few common examples of this motif.

In his book Taste Matters, John Prescott suggests that there’s an evolutionary reason we crave that balance: A piece of fruit that’s ripe has that same perfect-tasting sweet-sour proportion, while an under- or overripe fruit tastes out of balance.

But sourness is not a simple phenomenon. When you squeeze a lemon into a drink, you’re adding citric acid, which carries a particular taste that’s not just sour but a distinctive type of sour. A lime gives a drink a different kind of sourness, since it contains not only citric acid, but also malic acid and a small but significant amount of succinic acid, each of which adds something different. Still another type of acidity comes if you mix a cocktail with champagne or vermouth, which contain tartaric acid from the wine grapes they’re made with.

Contemporary bartenders, in their tireless pursuit of delicious concoctions, have realized that fruits and wines aren’t the only ways to get those acids into a drink. Cooks don’t grab a salty ingredient to get salt into a dish; we short-cut to the pure form. Citric, malic, tartaric, and other acids are sold in their pure powder forms on the Internet and can be added to cocktails in milligram amounts to precisely dial in the strength and type of acidity a bartender wants, just like salting a food.

“I would never have called myself a daiquiri fan before,” says new daiquiri enthusiast Dr. Rebecca Whelan. “I harbored bad associations of the drink as tending toward the overly sticky and sweet, relying on flashy color to mask poor quality and craft. The daiquiri [at Cleveland’s Spotted Owl] is impeccably balanced and complex. The presence of lactic acid in the lime juice is unlike anything I’ve experienced in a cocktail before, and it works perfectly, with layers of flavor that are both bright and deep.”

Of course, if bartenders are doing it right, you may not notice that your lime has secretly been replaced by a special mixture of acids. The trick is mimicking the natural acid balance of a fruit, enhancing rather than distorting the harmony of the drink, and working within our expectations of what a properly balanced drink is.

Most of the bartenders interviewed for this story have been playing around with isolated acids (citric acid at least) for a few years, inspired by recipes found online or trips to the home-brew store. For many, the publication of Dave Arnold’s book Liquid Intelligence in 2014 moved their experiments forward, as Arnold printed his recommended blend of acids—not just citric—to emulate lime juice. This technique has allowed bartenders to make better batched cocktails and clarified juices.

THE PROBLEM WITH ORANGES

At many cocktail bars, the old-fashioned has rocketed in popularity over the last few years. Classically made, it contains just whiskey, bitters, and sugar and gets much of its character from an aromatic garnish of orange peel. That popularity has a side effect: Dozens of oranges daily are stripped of their zesty peel, leaving a surplus of orange juice, which bars have little use for. The juice of the orange is very rarely called for in either modern or classic cocktails, because it isn’t nearly as acidic as lemon or lime juice and can make drinks turn out flabby and watery. Many bars end up discarding the peeled oranges entirely, but increasingly, some venues are acid-jacking the juice instead—dissolving in small, precise amounts of pure versions of the same acids that are in lime juice, to give that sweet fresh orange juice the strength of lime.

Nick Detrich did that when he developed drinks at Cane & Table in New Orleans: “Since we use a great deal of orange peels, but not much juice, we have two cocktails on our happy hour list that use an ounce and a half of orange juice and we wanted to balance the pH on those drinks. We use a blend of malic and citric acid because the green apple Warhead [candy] qualities of the malic add a nice vibrant freshness that is a great counterpoint to the very drying citric. We experimented with tartaric acid as well, but it added a weird dustiness.”

The Blood and Sand is one of the few classic cocktails that requires orange juice, and as a result it’s widely considered a challenging or unbalanced drink. Nick Kennedy of Civil Liberties in Toronto makes his with orange juice he spikes with citric and malic acid, just as Detrich does, changing his ratio of acids depending on the seasonal sweetness of the orange juice and tasting it against the acidity of lemon juice.

At Momofuku Ko in New York, Channing Centeno added citric acid to the house grapefruit syrup and to orange juice so he could avoid having to include limes. He says, “Instead of adding a half-ounce of lime to an already seven-ingredient drink to brighten a cocktail, why not just fortify the acidity in one of the existing ingredients?”

At Cassia in Santa Monica, California, Kenny Arbuckle deconstructs and reconstructs oranges by blending orange peels and juice together, removing the solids from the peel, then adding citric and a touch of phosphoric acid. “The point of acidifying the OJ,” he says, “is so we don’t have to add another acid, like lemon or lime, that would alter the flavor of the drink.” Of course, it’s not the exact same juice anymore. Arbuckle says, “The acidified OJ is texturally smoother, as the pulp is removed with the solids. It has a much sharper acidity than typical citrus. The flavor is still very orangy—part of the point in using the oil in the peel. The blending of the peels into the juice helps keep the flavor.”

FRANKENFRUIT

But why bother hand-building acidity to imitate limes when you can buy limes all year round? One issue is that lime juice begins losing its fresh flavor as soon as it’s squeezed, and a cocktail made with yesterday’s juice tastes stale. This is especially pronounced in the wake of another trend that’s sprung up within the last few years: In order to speed up service at craft cocktail bars, some bartenders are premaking their cocktails and putting them into bottles and kegs. They initially focused on citrus-free drinks, like the Negroni and the gin and tonic, but soon started seeking ways to bottle citrus-based cocktails without relying on temperamental citrus juice.

Cameron Brown of the Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, has made large batches of cocktails in advance for events, using an acid blend instead of citrus juice, since he wouldn’t be able to squeeze enough fresh juice the same day (and wouldn’t want to use oxidized juice from the previous day). His recipe calls for citric and malic acid with just a drop of acid phosphate.

Brown says, “The citric gives you the up-front acidity, but lacks the pucker feeling I need from malic on the back end. The acid phosphate rounds out the back end and creates a nicer texture and mouthfeel.” To compensate for the lack of actual juice, he says, “I tend to express some kind of citrus oil on top of the drink.”

Aaron Polsky of Los Angeles’ Harvard & Stone makes kegs full of cocktails using “the Dave Arnold recipe of 4 percent citric, 2 percent malic, 0.04 percent succinic” to simulate the acidity of lime juice for batched kegged cocktails for festivals and bars. Polsky then adds a custom-made combination of makrut (kaffir) lime oil and distillate—concentrated, isolated lime flavor—to the acid mixture to make a stable lime juice substitute. Not only will this formula not degrade over time, but it allows him to control the amount of water in his citrus mixture, depending on the final use of the drink (he says this is handy for making snow cones, where you want limited water content), or make a flavored cordial or sour mix of sorts from it.

ALL OF THE ACID, NONE OF THE JUICE

Other bartenders use added acids to achieve high acidity without any citrus taste, real or imitated. Alex Riddle of Roka Bar in San Francisco makes a cocktail that includes buckwheat shochu (a Japanese distilled spirit), squid ink, and white truffle oil, plus citric acid. He says, “We wanted the emphasis to be on the deep savory and umami flavors. It needed some sort of acid to balance the richness of the truffle and shochu. I originally tried using lemon juice, but found it to be both too full and too recognizable a flavor, ultimately taking away from the nuance of the other ingredients. We settled on a 7 percent citric acid solution, which provided enough acid to balance the cocktail, but was also simple and unassuming enough to allow the main components to shine through.”

Vlad Novikov of the Elixir Lounge in Chicago uses a clear sweet-and-sour mix of sorts, combining citric, ascorbic, and malic acids, without a citrus flavor. He says of his combination, “Adding malic acid helps dissociate the flavor of lemon that people get from citric acid sometimes, and adds a little depth.” At first, he says, he used chemical acidity constants (pKₐ) to calculate the exact theoretical amount of citric, malic, and ascorbic acids to replicate a specific citrus juice, “before realizing it was easier to just use my mouth to measure.”

Jacques Bezuidenhout of Forgery in San Francisco uses acid phosphate (a solution based on phosphoric acid) to replace lemon juice in a version of a Vampiro cocktail that includes crème de cassis. He says, “Lemon juice really muddied up the color of the cocktail and dominated some of the delicate flavors, so the acid phosphate added the desired acid to balance out the cocktail, allowing it to retain clarity in the glass.”

A LACTIC COLLABORATION

At the Spotted Owl in Cleveland, owner Will Hollingsworth adds lactic acid (a flavor we associate with fermentation, particularly fermented milk) to lime juice, which gives the bar’s popular daiquiri what he calls “creaminess” as well as changing the perception of the drink’s acidity.

To develop the drink, Hollingsworth worked with Dr. Rebecca Whelan, who is a regular customer as well as an associate professor and chair of chemistry and biochemistry at Oberlin College. Whelan says, “One evening when I was enjoying a cocktail at the Spotted Owl, he asked for my help interpreting a peer-reviewed research report. At the heart of the paper were observations about different acids in beverages and how those acids are perceived.” On the back of a Spotted Owl menu, Whelan and Hollingsworth wrote out chemical formulas to come to an understanding of what exactly the researchers had discovered.

“Her guidance on our daiquiri was invaluable,” says Hollingsworth. “Because of the particular anionic pairing of citric acid and lactic acid, the addition of a dash of lactic acid to the lime juice has the effect of actually raising the pH of the lime juice (from 2 to about 2.5), making it less acidic in absolute terms.” However, lactic acid also interacts with the drinker’s saliva, making the drink feel more astringent, “making it less viscous, and thus increasing a drinker’s perception of acidity. So despite the fact that in absolute terms, the lime juice is becoming less acidic, it’s being perceived as having a deeper sourness than it otherwise would have.”

SEARCHING FOR CLARITY

In a cocktail with carbonation, any particles of fruit pulp will turn it into a frothy mess, so some bartenders have become obsessed with getting out all the solids from juices.

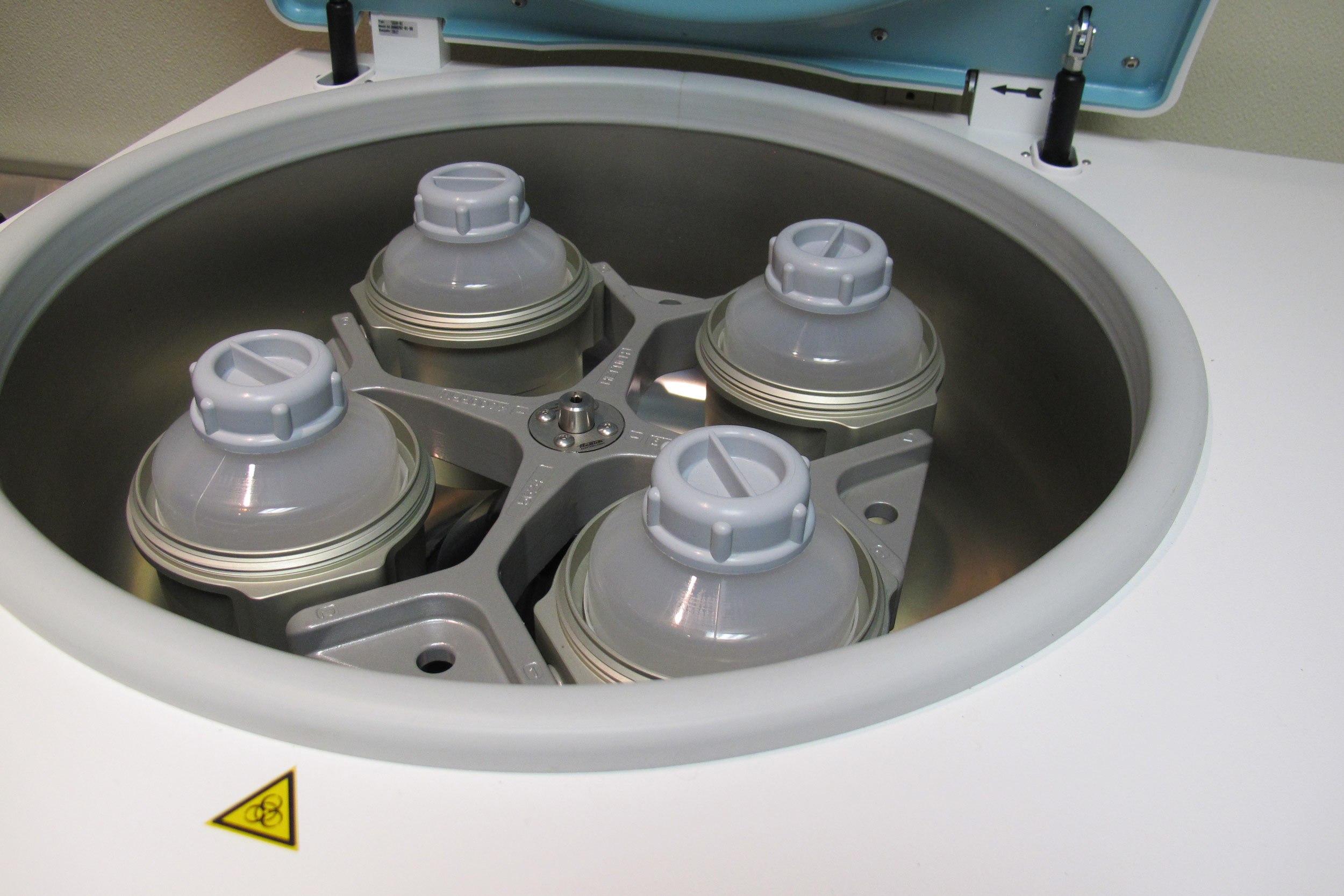

When high-tech bars use centrifuges to clarify juices, the pulpy solids are removed, which can reduce the juice’s acidity. Judicious reacidification through the addition of various powdered acids can bring them back to their original levels of sourness.

At Midnight Rambler in Dallas, Chad Solomon uses a centrifuge to clarify all the fresh ingredients that go into his carbonated beverages in order to reduce bubble-killing nucleation points.

Solomon says, “The clarification strips down the fresh ingredient to a leaner, cleaner version of itself that is still brimming with aroma. The clarified product is then enhanced with acid and [fructose or sucrose] to enhance flavor and mouthfeel.”

His imagination was sparked when he first saw Dave Arnold make a carbonated gin and tonic (pre-centrifuge) around 2007. He was further inspired by Darcy O’Neil’s book Fix the Pumps, which discusses alternative acidulants in the context of the soda fountain.

Solomon chooses which acids to use based on “the composition of the fresh ingredient as well as relative astringency, to properly enhance flavor and mouthfeel. I like to employ citric acid where the predominant acid is citric acid, such as orange, grapefruit, lemon, lime, pineapple, mango. For apricot, peach, pear, strawberry, apple, and watermelon, use malic acid. Tartaric or fumaric acid should be employed for grape, cherry, and banana.” He also supplements those acids with small amounts of phosphoric acid “for its flavorless, bone-dry astringency, to enhance mouthfeel.”

At Chicago’s The Aviary, Micah Melton uses a blend of acids in many of the drinks on the menu, both for carbonated cocktails and, in some cases, just to achieve a particular taste. “We just did a hot sauce-passion fruit clarification . . . it looks like champagne and tastes like ^%$**@$^@$*!!!!!,” he writes. He uses at least two acids per clarified fruit, to vary the effect; typically citric acid and one other, such as tartaric acid to give a “green grape” note, or fumaric acid for its “softer apple-like acidity.”

ACID TESTING

[Ed note: After Camper English delivered his story to the Cook’s Science team, senior editor Paul Adams began developing his own acid-hacked cocktail recipes for the home cook. The following is from his perspective.]

Back in the test kitchen, we were curious to give these acid-hacked cocktails a try. We started by tasting the various acids on their own, dissolved in water solutions, to get a feeling for their different characters. Citric acid had a medium impact and a puckery, drying finish. Malic acid tasted much stronger, with a hint of tart green apple—“like a Warhead candy,” noted one taster. Ascorbic acid was the mildest tasting and tartaric the strongest, also featuring a “creamy” taste. Succinic acid was the worst, tasting like some acutely bitter inedible resin or mineral. That must be why it’s only used in tiny doses. And the tasting notes on lactic acid—which we all love when it shows up in pickles and yogurt—included “bitter,” “like Fernet,” and “hint of bile.” Tasting acids neat is definitely not the most pleasant way to experience them, but it’s educational.

Next, I set out to do what seems like a natural starting point for hacking cocktails with powdered acids: tweaking other juices to give them the same acidity as lime juice. Flavorful and versatile, lime contributes more complexity than lemon juice and shows up in many cocktails. In his remarkable book Liquid Intelligence, which played a significant role in spreading the acid gospel, Dave Arnold gives a formula for conferring lime acidity on orange juice: For every liter of OJ, dissolve in 32 grams of citric acid and 20 grams of malic acid.

I squeezed a bunch of oranges and tried the recipe. The orange juice’s fragrance was unchanged, and it still had the round sweetness of fresh OJ, but at the same time it had the mouth-puckering bite of lime! Arnold also recommends adding a fraction of a gram of succinic acid, to create a more realistic simulation of the actual acid balance in a lime. When I mixed in the tiny quantity of succinic acid, it added an additional sharp tartness on the tip of the tongue that perfectly completed the lime effect.

I used citric, malic, and succinic acids, in various proportions, to make lime-acidified versions of grapefruit juice and apple juice as well, and then I started mixing them into cocktails.

A vast number of classic cocktails call for lime juice, so it was easy to find uses for my new lime substitutes. I put lime-adjusted orange juice in a margarita, lime-adjusted grapefruit juice in a daiquiri, lime-adjusted apple juice in a Jack Rose variant. In every case, the acid-adjusted juice did its job of lending the drink bright acidity, but also contributed some of its own fruit character.

After a delightful video conference session in which the Boston kitchen crew mixed and tasted cocktails while I supervised from my New York couch, we settled on two favorites: the Creema di Leema, a friendly, frothy cocktail using gin and acid-adjusted orange juice along with vanilla and cream; and the French 56½, made with gin, lemon, and soda, with tartaric and lactic acids added to give the impression of a sparkling wine.

Devising cocktails with acids as freestanding ingredients, rather than in the somewhat familiar form of simulated lime juice, turned out to be unexpectedly difficult. When a trial mixture tasted not quite right, I could tell it was out of balance, but it was strangely tricky to tell whether it needed more or less acid! Especially when lactic and tartaric were involved. More than once I was sure a recipe needed less acid, but when I made a reduced-acid version, it tasted wrong; and when I made a version with increased acid, suddenly everything came into balance.

With the addition of brand-new fundamental ingredients like these to the pantry, it’s necessary to play around to develop a real sense of them. Like being able to hear whether an out-of-tune note is too sharp or too flat, the ability gets better with practice.

GETTING STARTED WITH ACIDS

Here are a few pointers to help you start learning the acid ropes in your home kitchen or bar.

Get yourself a high-precision scale. The kitchen scale you have can only measure in increments of 1 gram, or perhaps 0.5 gram. Which is great for most cooking, but with these ingredients, a little is all you need—and you want to be able to measure that little precisely. The difference between 0.1 gram and 0.2 gram can make a big difference. You can get a good pocket-size scale for less than $20.

Start with a small selection. Citric acid and malic acid make a good starter kit: They’re common, affordable, versatile, and last but not least, they dissolve easily. Add straight citric for lemony acidity, straight malic for Granny Smith acidity, and a 2:1 citric-malic blend to emulate lime.

Taste them in sugar. To get to know your new acids, you’ll want to sample them, but not straight—too sour! You can mix them into water, but white sugar is a nice alternative that showcases each acid’s character. Mix 3 grams of a powdered acid (or combination of acids) into 100 grams of white sugar, then taste.

Swap them in. Try replacing lemon juice in a recipe with citric acid. Lemon juice is a solution of about 5 percent citric acid, so you can mix up faux lemon juice by dissolving 5 grams of citric acid in 100 grams of water. Then use it ounce-for-ounce in place of juice.

Styled food photography by Steve Klise.

Test kitchen photography by Kevin White.