In this weekly series, associate editor Tim Chin and test cook Sasha Marx take you behind the scenes of Cook’s Science and give you a glimpse into our recipe development process, from how we come up with recipe ideas, to test kitchen failures, to discoveries we make along the way. This week, Tim gives the lowdown on how he comes up with ideas for new Cook’s Science recipes.

How do we develop recipes here at Cook’s Science? Well, most of our recipe development starts long before we set foot in the kitchen. It starts with ideas. Lots and lots of ideas.

This week I’ve had a lighter workload—which feels kind of weird, given our usual pace. Between editing recipes, writing this article, and playing fetch with the office dogs (I’m looking at you, Ollie), I’ve also been brainstorming new recipes. That got me thinking big picture: Where do the ideas for the recipes we develop come from?

From my perspective, our recipes have one of two main starting points.

A lot of them start with a technique or some really fascinating kitchen science. Sasha, Dan, and I often find ourselves fixated on a particular cooking technique that will drive our recipe development. This can be as simple as freezing egg whites for convenient use in cocktail recipes (see: Whiskey Sour and Aperol Flip) or as esoteric as making a ganache out of water and chocolate. For my hand-pulled noodle recipe, I spent considerable time—literally weeks—refining the technique for pulling the noodles as well as tweaking my formula for the dough. Most recently, I spent a month diving into the technique of curing egg yolks in salt and sugar—dry cures, wet cures, and both sweet and savory applications. This sort of recipe development allows for broad, deep exploration (for example, my first tests of cured egg yolk techniques resulted in Dan, Sasha, and I tasting 25 different samples to narrow down our preferences) and often provides insight into how small changes in a technique can affect the flavor or texture of a recipe. For our Caramel-Cured Egg Yolks, it turned out that just a few hours’ difference in curing time had a major impact on the texture of the yolks.

For others, the starting point is a single ingredient or a specific dish. Sometimes these accompany a story or article (see: tortillas and cornbread to accompany our feature on nixtamalization; Brazilian cheese bread to go with our feature on manioc), but other times these recipes are driven by our own personal interests. This is my favorite kind of recipe development. From Sasha’s eggplant deep-dive to his upcoming beet recipes, these recipes demonstrate the broad range of an ingredient’s potential. We take an ingredient and ask questions like: “What can this food do?”; “How is it used?”; “How do you eat it?”; “How can you transform it?”; and “How can it transform other foods?” We get inspiration any way we can. For me, I have conversations with other test cooks here at ATK as well as experts in the field, thumb through cookbooks, scour the web, and scroll through Instagram for hours.

My biggest ingredient-driven recipe project to date was developing recipes to accompany the koji feature. I knew I wanted to grow koji on different grains and proteins, and make my own shio koji and amazake. But I also wanted to bring something of myself to the project. I tinkered and tested, shared numerous conversations with Jeremy Umansky, and suffered some hard-fought failures (R.I.P. koji French fries). In the end, my moment of inspiration came from a sacred place: my shower—because all my greatest ideas have come to me in the shower. Koji Fried Chicken became a hit, and to this day ranks among my team’s favorite recipes. (Not to mention, Koji Turkey.) This type of organic development allows for freedom of ideas and expression—which, for me, is the best and most important part about cooking. We’re just starting to think about potential directions for recipes to accompany an article about salt, and I’m excited to see what we’ll come up with.

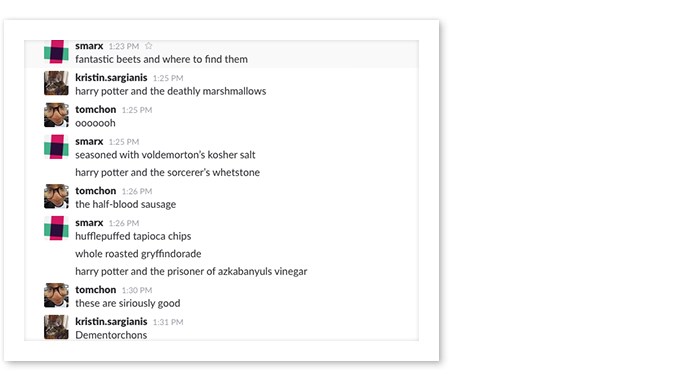

I would be remiss if I did not mention a third—though no less important—pseudo-category of brainstorming: pun-driven recipes. If you haven’t noticed by now, our team loves a good play on words. It seems like we can’t go five minutes in our office without Sasha blurting out some absurdly phrased dish title, most of which I come to love. Some notable examples: Beet Wellington, Boo-dino (Romantic) Pudding, Koji-nita Pibil, Matzo-rella, and my personal favorite—Pigs in a Blanquette. In fact, our whole team has jumped on the pun-recipe bandwagon, as evidenced by this recent Harry Potter-themed Slack conversation:

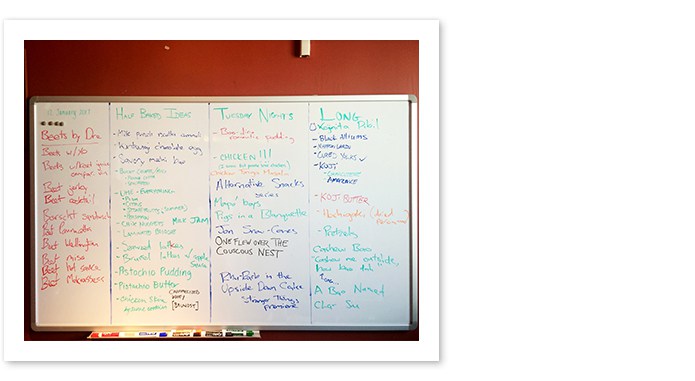

Most of these ideas will live out the rest of their days on the whiteboard in our office, never to be published, forever to be cherished. But they serve as an important reminder for our brainstorming process—to let loose and get those creative vibes going. All ideas are good ideas. Alfred Hitchcock once said that “puns are the highest form of literature”. We’ve gotten this far punning around, so maybe Sasha’s on to something.

As you might have gathered, our team generates a lot of ideas for recipes. That whiteboard is pretty full. When it comes to deciding which recipes to develop and publish, the process is democratic. We discuss ideas as a team before moving forward. No idea is ever too precious, too stupid, too hard, or too easy. But, in the end, it must bring something enriching to our readers: A cool technique, a fresh way of looking at an ingredient, or simply a food that deserves more recognition. Above all, the final product has to taste good. But that’s our job, and as Sasha often says during our brainstorms, no matter what, “You’re gonna love it.”

Photography by Steve Klise